It seems to be a common theme through the history of software that some titles, get bought, sold, rebranded, integrated, and discontinued by a number of companies. I find it interesting to find out a popular software title’s humble beginnings. Often when a piece of software gets bought, the file formats don’t change much, at least at first.

A little shareware program called iView started out by a company called Script Software in 1996. They later changed their name to Plum Amazing. iView then became iView Multimedia, then an iView MediaPro version before it was bought by Microsoft where they changed the name to Expression Media. After a couple years the software was bought by Phase One and then discontinued. Let’s take a look at the history.

iView, according to their website in 1997, is simply the easiest and fastest way to view and catalog pictures for the Mac. The software initially only worked on the Macintosh and the Catalog file it produced did not have an extension. But they did have a Type/Creator code. A catalog produced by version 2 of the iView software was IVWc/IVW2.

% hexdump -C iView2-s01 | head

00000000 00 00 00 05 30 32 35 69 47 4f 53 58 3a 4c 69 62 |....025iGOSX:Lib|

00000010 72 61 72 79 3a 41 70 70 6c 69 63 61 74 69 6f 6e |rary:Application|

00000020 20 53 75 70 70 6f 72 74 3a 41 70 70 6c 65 3a 69 | Support:Apple:i|

00000030 43 68 61 74 20 49 63 6f 6e 73 3a 46 72 75 69 74 |Chat Icons:Fruit|

00000040 3a 47 72 65 65 6e 20 41 70 70 6c 65 2e 67 69 66 |:Green Apple.gif|

00000050 03 46 44 63 00 00 0f ef 03 46 44 63 08 93 65 58 |.FDc.....FDc..eX|

00000060 00 01 5c 50 00 01 5a c8 68 ff f7 40 08 93 65 4b |..\P..Z.h..@..eK|

00000070 08 13 9a c0 ff d1 3a 80 00 a3 c8 a0 00 00 28 00 |......:.......(.|

00000080 00 05 48 64 00 00 a0 24 00 00 39 ec 00 00 00 0a |..Hd...$..9.....|

00000090 08 93 65 64 44 00 00 24 3d 14 51 84 3d 9d 74 bc |..edD..$=.Q.=.t.|

The iView format is a proprietary binary format used to store a catalog of multimedia formats with their metadata and thumbnail. The media viewer had support for quite a few popular formats. The file seems to have paths to each of the files it has cataloged, so some of these iView files can get pretty large.

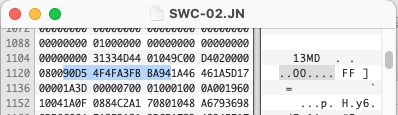

In 2003 the iView software was ported to Windows. With that brought a formal extension to the catalog format. This was also the time the iView software made the switch from the classic MacOS to MacOSX and extensions were also encouraged at this time. iView had two different version a standard shareware version and a Media Pro version, each had their own version numbers. iView MediaPro was not compatible with Macintosh 68K machines or systems earlier than 8.6. The last Media Pro version was version 3.8.6. You can get most of the old software versions here.

% hexdump -C iViewPro302-s01.ivc | head

00000000 00 00 00 00 30 32 35 69 46 53 4d 21 00 00 00 2e |....025iFSM!....|

00000010 66 6c 64 72 00 00 00 2e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 06 |fldr............|

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 3c 72 6f 6f 74 3e 42 4c |........<root>BL|

00000040 44 4f 00 00 00 0c 31 00 02 00 00 00 01 01 00 00 |DO....1.........|

00000050 00 00 55 53 46 33 00 00 00 02 01 03 43 4d 52 53 |..USF3......CMRS|

00000060 00 00 01 ed 01 00 00 02 0a 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000070 00 02 f2 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 a2 01 00 00 |................|

00000080 00 00 02 01 03 00 00 00 a1 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000090 00 00 48 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 03 01 00 00 |..H.............|

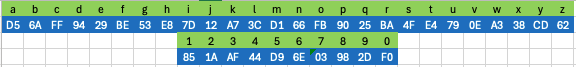

This time with an extension, IVC, but with a familiar pattern at the beginning. The string 025i, hex values “30323569” at byte 4. The iView files from previous versions have the same bytes, but only version Media Pro 2 & 3 files match an existing PRONOM identification.

% sf iViewPro302-s01.ivc

filename : 'iViewPro302-s01.ivc'

filesize : 3757

modified : 2025-09-17T17:39:27-06:00

errors :

matches :

- ns : 'pronom'

id : 'fmt/647'

format : 'Microsoft Expression Media'

version : '2'

mime :

class : 'Presentation'

basis : 'extension match ivc; byte match at [[4 4] [3737 16]]'

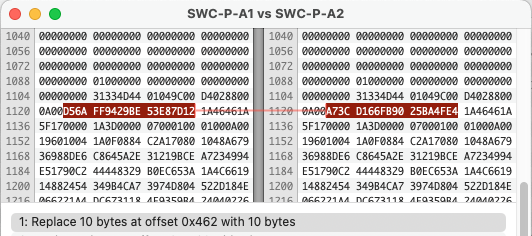

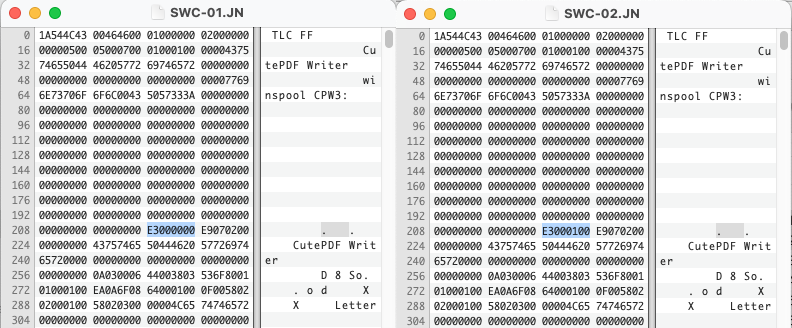

These are iView Media Pro files, why are they identifying as Microsoft Expression Media files? That is because Microsoft bought iView Media Pro on June 27, 2006. Microsoft rebranded the software as Expression Media, not to be confused with Expression Studio. It was available for Windows and Macintosh, but not everyone was happy with the purchase. Version 1 of Expression Media was released the next year and was a free upgrade for iView Media Pro users. The format doesn’t appear to have changed much at all. In fact a comparison of an iView Media Pro 3 file with no content and an Expression Media 1 file are practically identical.

% hexdump -C Expression1-s01.ivc | head

00000000 00 00 00 00 30 32 35 69 46 53 4d 21 00 00 00 2e |....025iFSM!....|

00000010 66 6c 64 72 00 00 00 2e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 06 |fldr............|

00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 3c 72 6f 6f 74 3e 42 4c |........<root>BL|

00000040 44 4f 00 00 00 0c 31 00 02 00 00 00 01 01 00 00 |DO....1.........|

00000050 00 00 55 53 46 33 00 00 00 02 01 03 43 4d 52 53 |..USF3......CMRS|

00000060 00 00 01 ed 01 00 00 02 0a 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000070 00 02 f2 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 a2 01 00 00 |................|

00000080 00 00 02 01 03 00 00 00 a1 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000090 00 00 48 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 03 01 00 00 |..H.............|

The next year brought a version 2 of Expression Media, often found bundled with a Special Edition of Office 2008 for Mac, but also a standalone product for Windows. But the catalog format remained the same.

% hexdump -C Expression2-s01.ivc | head

00000000 00 00 00 04 30 32 35 69 3a 43 3a 5c 44 4f 43 55 |....025i:C:\DOCU|

00000010 4d 45 7e 31 5c 41 4c 4c 55 53 45 7e 31 5c 44 4f |ME~1\ALLUSE~1\DO|

00000020 43 55 4d 45 7e 31 5c 4d 59 50 49 43 54 7e 31 5c |CUME~1\MYPICT~1\|

00000030 53 41 4d 50 4c 45 7e 31 5c 57 69 6e 74 65 72 2e |SAMPLE~1\Winter.|

00000040 6a 70 67 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |jpg.............|

00000050 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

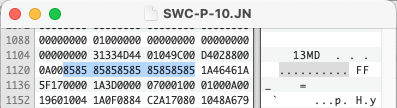

Even though all of these versions have the same 4 bytes at the beginning, not all of them match the current PRONOM signature. fmt/647 is specifically for Expression Media version 2 files, but also identifies iView Media Pro 2 & 3 and Expression Media 1 files. It doesn’t identify earlier files because the signature is also looking for some bytes near the end of the file.

% hexdump -C iViewPro302-s01.ivc | tail

00000e90 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 53 56 61 72 00 00 00 |.........SVar...|

00000ea0 04 00 00 01 f4 30 32 35 69 00 00 00 08 |.....025i....|

There is the same 4 bytes at the end of the file as well. There is also a string used in the signature at the end, “SVar”. Not sure what the string is used for but it is not in earlier versions.

% hexdump -C iView157-01 | tail

00000420 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 30 32 35 69 |............025i|

00000430 00 00 00 08 |....|

And the even earlier versions are missing the “025i” at the end.

% hexdump -C iView2-s01 | tail

000062b0 2a ae ed d4 1a eb d4 04 c4 88 76 88 c4 d6 d4 04 |*.........v.....|

000062c0 c4 79 69 79 c4 d6 d4 04 c4 78 67 78 c4 ec d4 04 |.yiy.....xgx....|

000062d0 81 d4 f1 d4 00 ff |......|

Microsoft Expression Media was short lived. Microsoft decided to sell off the software to Phase One in 2010. Phase One is the developer of Capture One, a professional photo editing program. It makes sense they would want a cataloging tool to go with their flagship product. Phase One retained the name Media Pro from the original iView Media Pro software.

Phase One took the software and did make modifications, starting with the extension used to store the catalogs. They also decided to adjust the format slightly, changing the “025i” bytes to “030i”.

% hexdump -C PhaseOneMediaProv1.mpcatalog | head

00000000 00 00 00 05 30 33 30 69 4a 4d 61 63 31 30 37 3a |....030iJMac107:|

00000010 4c 69 62 72 61 72 79 3a 41 70 70 6c 69 63 61 74 |Library:Applicat|

00000020 69 6f 6e 20 53 75 70 70 6f 72 74 3a 41 70 70 6c |ion Support:Appl|

00000030 65 3a 69 43 68 61 74 20 49 63 6f 6e 73 3a 46 72 |e:iChat Icons:Fr|

00000040 75 69 74 3a 47 72 65 65 6e 20 41 70 70 6c 65 2e |uit:Green Apple.|

00000050 67 69 66 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |gif.............|

00000060 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

The Phase One Media Pro software uses the extension MPCATALOG, but can also open the older IVC catalogs as well.

% sf PhaseOneMediaProv1.mpcatalog

filename : 'PhaseOneMediaProv1.mpcatalog'

filesize : 21353

modified : 2025-09-16T20:37:07-06:00

errors :

matches :

- ns : 'pronom'

id : 'fmt/648'

format : 'Media View Pro'

version :

mime :

class : 'Presentation'

basis : 'extension match mpcatalog; byte match at [[4 4] [21329 16]]'

MPCATALOG files are identified in PRONOM using a similar signature as the one used for the IVC files. Although the name of the format isn’t quite right, MediaPro is probably a better name.

So it seems the identification is already available in PRONOM for the later MediaPro files, both iView MediaPro and Expression Media, and a second identification for the PhaseOne catalog. So we will need to either adjust the identification to include the earlier iView versions and adjust the names or we can create a new signature for the older versions. It would be good to find out what version added the change to the format, but with all the different software versions, it might be hard to nail down.

Enjoy some samples.