Without divulging any youthful indiscretions, I recently was going back through some of my personal archives and came across a disc I burned around 2002 with some music stored on it. Normally I would find MP3 files, but in this case the file had a ACE extension. I remembered the format as an alternative to the common RAR or ZIP format often used to compress content for transporting (sharing) around the internet. I did what I normally do when something is compressed and reached for 7zip. But to my surprise, it threw an error.

% 7z l sample.ace

Scanning the drive for archives:

1 file, 12501419 bytes (12 MiB)

Listing archive: sample.ace

ERROR: sample.ace : Can not open the file as archive

7zip usually can handle most common archives but a part of me remembered there was two versions of WinACE back in the day. Version 1 which was a free version and Version 2 which was for paid users of WinACE. How do I know which version I have is the question I frequently find myself asking. First was to check the PRONOM registry.

% sf sample.ace

---

siegfried : 1.11.2

scandate : 2025-09-11T09:01:25-06:00

signature : default.sig

created : 2025-03-01T15:28:08+11:00

identifiers :

- name : 'pronom'

details : 'DROID_SignatureFile_V120.xml; container-signature-20240715.xml'

---

filename : 'sample.ace'

filesize : 12501419

modified : 2025-09-11T09:04:36-06:00

errors :

matches :

- ns : 'pronom'

id : 'UNKNOWN'

format :

version :

mime :

class :

basis :

warning : 'no match'

Nope, this format is not known to PRONOM. Lets try another tool.

% file sample.ace

sample.ace: ACE archive data version 20, from Win/32, version 20 to extract, solid

Ok, so the file tool knows it is a version 2 ACE file and requires version 2 to extract. Good info from a file identification tool. Now lets see what we can find to extract this file on MacOS. The website Winace.com is long gone as this compression tool lost popularity and the final release was over 14 years ago. Looking at the website in the WaybackMachine we can see some downloads available. One being UnACE for Mac OS X, which upon further review, only works for the older PowerPC Mac’s. There is an open source version of unace for Linux, but it only supports version 1, the free version of the format.

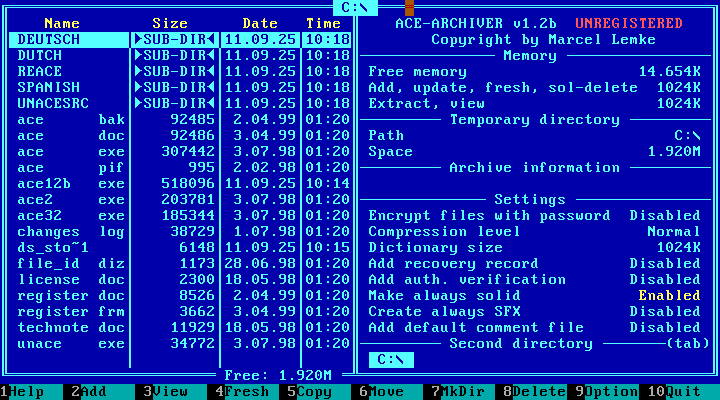

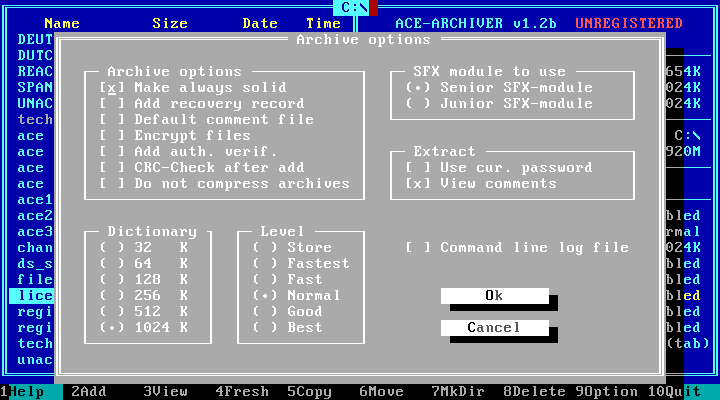

Below is a screenshot of the DOS version of the ACE software. Created by Marcel Lemke.

It might be good to mention that WinRAR used to support the ACE format, but with WinACE support ending years ago and with some new vulnerabilities and folks using it for malware, support was dropped in 2019.

Luckily, I still have my PowerMac G5 lying around waiting for this very situation. After a quick install, unace was able to unarchive my music and I was able to listen to some of my favorite songs from 23 years ago. I still wanted to find a modern solution and later discovered there is a python project which can read and extract bother versions. Acefile is a pure python, no-dependencies implementation of the UnACE format. I had a little issue installing on an older Catalina laptop, but worked well on later MacOS versions. Acefile has a few features that are helpful in not only extracting, but testing and dumping the headers of an ACE file. I did install WinACE in a Windows XP Virtual Machine to make a few samples, here is one of them.

% acefile-unace --test sample.ace

success test.tif

total 1 tested, 1 ok, 0 failed

The test feature works well to ensure the file is complete and can be extracted, but doesn’t give me much to go on for knowing the version. Lets try dumping the header.

% acefile-unace --header sample.ace

volume

filename sample.ace

filesize 12501419

headers MAIN:1 FILE:1 RECOVERY:0 others:0

header

hdr_crc 0x4900

hdr_size 44

hdr_type 0x00 MAIN

hdr_flags 0x8100 V20FORMAT|SOLID

magic b'**ACE**'

eversion 20 2.0

cversion 20 2.0

host 0x02 Win32

volume 0

datetime 0x5b2aae37 2025-09-10 21:49:46

reserved1 c8 51 62 e3 5b 80 00 00

advert b''

comment b''

reserved2 b'\x00e\x9c\xb1\xd8\x00\x03\n\x00\x00@\x08\x00test.'

header

hdr_crc 0x3626

hdr_size 39

hdr_type 0x01 FILE32

hdr_flags 0x8001 ADDSIZE|SOLID

packsize 12501328

origsize 25264236

datetime 0x5b2aadcd 2025-09-10 21:46:26

attribs 0x00000080 NORMAL

crc32 0x9290955a

comptype 0x02 blocked

compqual 0x03 normal

params 0x000a

reserved1 0x4000

filename b'test.tif'

comment b''

ntsecurity b''

reserved2 b''

This is very helpful. We can see the output shows the magic bytes, but also the e(xtraction)version and c(creating)version. We can also find this information in the open source unace technical documentation.

2 HEAD_CRC CRC16 over block up from HEAD_TYPE

2 HEAD_SIZE size of the block from HEAD_TYPE

up to the last byte of this block

1 HEAD_TYPE archive header type is 0

2 HEAD_FLAGS contains most important information about the

archive

bit discription

0 0 (no ADDSIZE field)

1 presence of a main comment

9 SFX-archive

10 dictionary size limited to 256K

(because of a junior SFX)

11 archive consists of multiple volumes

12 main header contains AV-string

13 recovery record present

14 archive is locked

15 archive is solid

7 ACESIGN fixed string: '**ACE**' serves to find the

archive header

1 VER_EXTRACT version needed to extract archive

1 VER_CREATED version used to create the archive

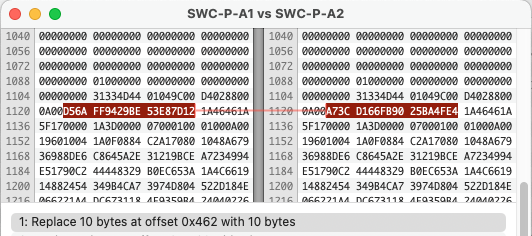

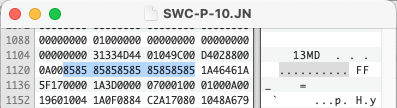

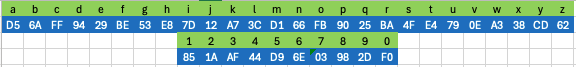

I think we have enough to go on to create a signature, we just need to see what the 1 byte versions number look like in an actual file.

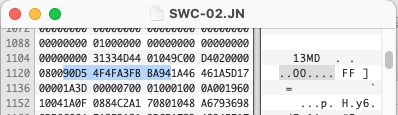

% hexdump -C sample.ace | head

00000000 00 49 2c 00 00 00 81 2a 2a 41 43 45 2a 2a 14 14 |.I,....**ACE**..|

00000010 02 00 37 ae 2a 5b c8 51 62 e3 5b 80 00 00 00 65 |..7.*[.Qb.[....e|

00000020 9c b1 d8 00 03 0a 00 00 40 08 00 74 65 73 74 2e |........@..test.|

00000030 26 36 27 00 01 01 80 50 c1 be 00 6c 80 81 01 cd |&6'....P...l....|

00000040 ad 2a 5b 80 00 00 00 5a 95 90 92 02 03 0a 00 00 |.*[....Z........|

00000050 40 08 00 74 65 73 74 2e 74 69 66 28 25 a4 89 04 |@..test.tif(%...|

00000060 fa 43 b1 05 49 0c a3 76 8e 16 a9 2c 92 44 34 8c |.C..I..v...,.D4.|

00000070 2c 12 e7 28 67 68 49 69 a7 92 4a 10 07 da 10 16 |,..(ghIi..J.....|

00000080 9c 16 4a 10 07 2b 9c ae 30 a9 50 c4 0a 69 51 a6 |..J..+..0.P..iQ.|

00000090 c9 64 a7 24 09 93 3d 81 26 31 a9 c2 68 32 c1 33 |.d.$..=.&1..h2.3|

As you can see above, we have our magic bytes **ACE** starting at the seventh byte and taking up seven bytes. Then two bytes after it both with the hex value 14. If we convert that hex value to decimal we get “20”. Let’s look at another:

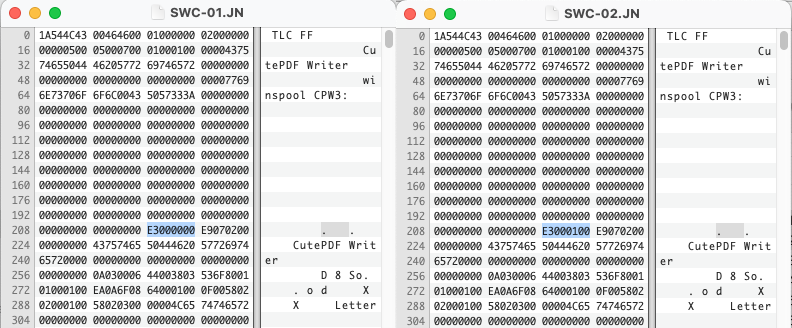

% hexdump -C sample2.ace | head

00000000 61 67 31 00 00 00 90 2a 2a 41 43 45 2a 2a 0a 0c |ag1....**ACE**..|

00000010 02 00 50 7c 31 26 d7 2b c0 48 af 83 ce d9 16 2a |..P|1&.+.H.....*|

00000020 55 4e 52 45 47 49 53 54 45 52 45 44 20 56 45 52 |UNREGISTERED VER|

00000030 53 49 4f 4e 2a 34 5f 24 00 01 01 80 00 00 00 00 |SION*4_$........|

00000040 35 00 00 00 3c 7c 31 26 10 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff |5...<|1&........|

00000050 01 05 0a 00 2a 55 05 00 61 75 64 69 6f 45 72 23 |....*U..audioEr#|

00000060 00 01 01 80 00 00 00 00 35 00 00 00 3c 7c 31 26 |........5...<|1&|

00000070 10 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff 01 05 0a 00 2a 55 04 00 |............*U..|

00000080 42 49 54 53 98 14 24 00 01 01 80 00 00 00 00 35 |BITS..$........5|

00000090 00 00 00 3c 7c 31 26 10 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff 01 |...<|1&.........|

Hmm, now we have two different values. “0A” converts to decimal “10” and “0C” converts to decimal “12”. So we can infer this ACE file was created in version 1.2 and requires at least version 1.0 to extract. Let’s try another:

% hexdump -C sample3.ace | head

00000000 c0 3f 2c 00 00 00 81 2a 2a 41 43 45 2a 2a 0a 14 |.?,....**ACE**..|

00000010 02 00 dc ad 2a 5b 23 52 89 e0 5b 80 00 00 00 65 |....*[#R..[....e|

00000020 9c b1 d8 00 03 0a 00 00 40 08 00 74 65 73 74 2e |........@..test.|

00000030 92 f3 27 00 01 01 80 54 c3 be 00 6c 80 81 01 cd |..'....T...l....|

00000040 ad 2a 5b 80 00 00 00 5a 95 90 92 01 03 0a 00 00 |.*[....Z........|

00000050 40 08 00 74 65 73 74 2e 74 69 66 28 25 a4 89 04 |@..test.tif(%...|

00000060 fa 43 b1 05 49 0c a3 76 8e 16 a9 2c 92 44 34 8c |.C..I..v...,.D4.|

00000070 2c 12 e7 28 67 68 49 69 a7 92 4a 10 07 da 10 16 |,..(ghIi..J.....|

00000080 9c 16 4a 10 07 2b 9c ae 30 a9 50 c4 0a 69 51 a6 |..J..+..0.P..iQ.|

00000090 c9 64 a7 24 09 93 3d 81 26 31 a9 c2 68 32 c1 33 |.d.$..=.&1..h2.3|

Again we have “0A” which converts to decimal “10” and hex 14, which converts to decimal “20”. So made with version 2.0 of the software, but made compatible with version 1.0 for extraction. One more:

% hexdump -C sample4.ace | head

00000000 8b d6 31 00 00 00 90 2a 2a 41 43 45 2a 2a 0b 0b |..1....**ACE**..|

00000010 02 00 cd b4 3e 26 4a e3 a1 80 32 4b c1 d9 16 2a |....>&J...2K...*|

00000020 55 4e 52 45 47 49 53 54 45 52 45 44 20 56 45 52 |UNREGISTERED VER|

00000030 53 49 4f 4e 2a aa 08 24 00 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 |SION*..$........|

00000040 00 00 00 00 83 b2 3e 26 10 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff |......>&........|

00000050 01 05 0a 00 2a 55 05 00 4d 75 73 69 63 77 73 27 |....*U..Musicws'|

00000060 00 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 83 b2 3e 26 |..............>&|

00000070 10 00 00 00 ff ff ff ff 01 05 0a 00 2a 55 08 00 |............*U..|

00000080 52 65 73 6f 75 72 63 65 93 75 25 00 01 01 00 00 |Resource.u%.....|

00000090 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 83 b2 3e 26 10 00 00 00 ff |.........>&.....|

Both extraction and creation version are hex “0B” which converts to decimal “11”. I would have assumed any version 1.0 version could extract anything created with later 1.x versions, but I guess that might not be true. I am not clear on all the versions released, so I am not sure how many versions I should include in a signature. I did look through some of the captured pages on the WayBackMachine and feel the last 1.x version was version 1.32.

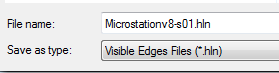

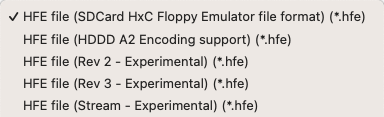

When building these signatures, it should be easy to create two signatures based on their extraction version. But should the creation version be a factor? Version 1.0 could look like this:

2A2A4143452A2A(0A|0B|0C|0D)(0A|0B|0C|0D|14)

This accounts for the versions 1.0 through 1.3 for extract version and 1.0 through 2.0 for creation version. Version 2.0 doesn’t seem to indicate minor versions with all 2.0 versions using decimal 14. So a signature could be:

2A2A4143452A2A1414

Both would start from offset 7 from the beginning of the file. Is there a better solution?

I will warn you, there are a couple of ACE formats out there which you may come across. One being an image/texture format for Microsoft Train Simulator. That might be for another day. There is another use of the ACE archive which is worth discussing. The Comic Book Archive file with the extension CBA will use the ACE archive for storing a series of images used in some Comic Book Readers. They are indeed ACE archive files, only having the different extension and a specific purpose. Maybe adding the CBA extension to the signature would be sufficient?

I am sure there are some other properties, seen above, of the ACE format we could discuss, encryption, the differences between Solid and SFX, and dictionary headers, but I think for now, identification of the format and the main version difference is sufficient. For now, check out my Github page for my signature proposal and a few samples I made.