Microsoft is never in short supply of file formats. They have made many changes over the years. Introduced lots of products, some lasting longer than others. The list is quite long.

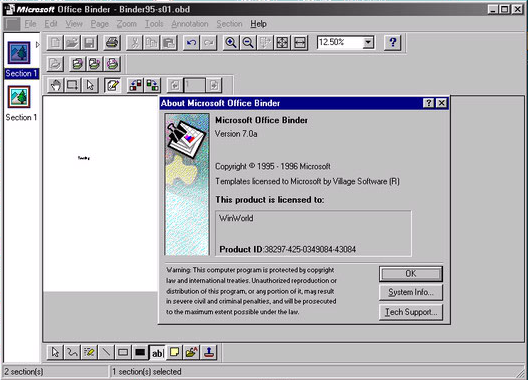

One such software was called Office Binder. Introduced with Office 95, it was a companion application to combine a number of OLE objects together in one “Binder”. Meant to be the digital version of an Office Binder one often uses for presentations or proposals.

You could add sections and include Word documents, Images, Powerpoint, Excel spreadsheets, basically any OLE object. Of course a Binder file itself was an OLE compound object. They had the extension OBD, and templates used OBT. The PRONOM registry has PUID’s for the different Binder versions, but there are some issues.

| PUID | Format Name | Format Version | Extension |

|---|---|---|---|

| fmt/237 | Microsoft Office Binder File for Windows | 95 | obd |

| fmt/240 | Microsoft Office Binder File for Windows | 97-2000 | obd |

| fmt/238 | Microsoft Office Binder Template for Windows | 95 | obt |

| fmt/241 | Microsoft Office Binder Template for Windows | 97-2000 | obt |

| fmt/239 | Microsoft Office Binder Wizard for Windows | 95 | obz |

| fmt/242 | Microsoft Office Binder Wizard for Windows | 97-2000 | obz |

filename : 'Binder95-s01.obd'

filesize : 5120

modified : 2024-08-08T21:24:34-06:00

errors :

matches :

- ns : 'pronom'

id : 'fmt/240'

format : 'Microsoft Office Binder File for Windows'

version : '97-2000'

mime :

class :

basis : 'extension match obd; container name Binder with name only'

Turns out only one of the PRONOM PUID’s has an actual signature, the others are placeholders. So when I run Siegfried on an Office Binder 95 file, it comes back as fmt/240 which points to an Office Binder 97-2000 file. It’s a simple signature, looking for an internal file named “Binder”, which is inherent of all the Binder file types.

<ContainerSignature Id="5500" ContainerType="OLE2">

<Description>Microsoft Office Binder File for Windows 97-2000</Description>

<Files>

<File>

<Path>Binder</Path>

</File>

</Files>

</ContainerSignature>

Taking a look inside the Office 95 Binder file, we can see the “Binder” file.

Path = Binder95-s01.obd

Type = Compound

Physical Size = 5120

Extension = compound

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

..... 316 320 [5]SummaryInformation

..... 144 192 Binder

..... 280 320 [5]DocumentSummaryInformation

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

740 832 3 files

hexdump -C Binder95-s01/Binder

00000000 90 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 |................|

00000010 00 00 00 00 a1 6a 8a 8e cc 55 ef 11 ab 06 00 0c |.....j...U......|

00000020 29 b1 b4 d0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |)...............|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 86 61 a6 |............@.a.|

00000040 0b ea da 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 40 86 61 a6 |............@.a.|

00000050 0b ea da 01 09 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000060 00 00 00 00 2c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 |....,...........|

00000070 ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff |................|

00000080 2c 00 00 00 2c 00 00 00 13 03 00 00 44 02 00 00 |,...,.......D...|

The bytes within a “Binder” file has some patterns, but nothing decipherable.

Microsoft Office Binder was only included in three versions of Office. Office 95, 97, and 2000. Let’s look at the other two versions.

Path = Binder97-s04.obd

Type = Compound

Physical Size = 5632

Extension = compound

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

..... 28 64 HdrFtr

..... 144 192 Binder

..... 260 320 [5]SummaryInformation

..... 404 448 [5]DocumentSummaryInformation

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

836 1024 4 files

Path = Binder2K-S01.obd

Type = Compound

Physical Size = 5632

Extension = compound

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

..... 28 64 HdrFtr

..... 144 192 Binder

..... 260 320 [5]SummaryInformation

..... 232 256 [5]DocumentSummaryInformation

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

664 832 4 files

It looks like version 97 and 2000 have an extra file. The “HdrFtr” file seems to reference a Header and Footer, which according to documentation was a feature added in Office 97.

What’s new in Office Binder 97

Office Binder makes it possible for you to group all your documents, workbooks, and presentations for a project in one place. To get started with Office Binder 97, add a new or existing document to your binder. Use the new Office 97 features while you work in a binder……. Print headers and footers for a binder

We can use the “HdrFtr” file within the container to differentiate between the 95 version and 97-2000 formats. Perhaps, a closer look at the DocumentSummaryInformation file in the future, might help with a more precise identification later. There doesn’t seem to be anything to distinguish an OBD file from a OBT template file, so those PUID’s may not be needed. The other format related to the Binder software has the OBZ extension. It is called a Wizard template file in some documentation, but I have been unable to find any type of “Wizard” functionality in the Office Binder Apps to generate a file. The OBZ format seems to have something to do with macros in Visual Basic. Luckily there are a few examples available on Office install disc‘s.

Path = CLIENT.OBZ

Type = Compound

Physical Size = 364032

Extension = doc

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

1995-07-05 17:25:15 D.... 7

1995-07-05 17:25:14 D.... 5

1995-07-05 17:25:13 D.... 4

..... 106 128 4/[1]CompObj

..... 20 64 4/[1]Ole

..... 8880 9216 4/WordDocument

..... 32 64 4/[3]View000

..... 492 512 4/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 236 256 4/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

1995-07-05 17:25:14 D.... 6

..... 17760 17920 6/Book

..... 20 64 6/[1]Ole

..... 0 0 6/[3]View000

..... 102 128 6/[1]CompObj

..... 3260 3264 6/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 192 192 6/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

..... 106 128 5/[1]CompObj

..... 20 64 5/[1]Ole

..... 8055 8192 5/WordDocument

..... 32 64 5/[3]View000

..... 7280 7680 5/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 220 256 5/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

1995-07-05 17:25:16 D.... 9

1995-07-05 17:25:15 D.... 8

..... 13857 14336 8/Book

..... 20 64 8/[1]Ole

..... 0 0 8/[3]View000

..... 102 128 8/[1]CompObj

..... 188 192 8/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 196 256 8/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

..... 854 896 Binder

1995-07-05 17:25:19 D.... 10

..... 80382 80384 10/Book

..... 20 64 10/[1]Ole

..... 0 0 10/[3]View000

..... 102 128 10/[1]CompObj

..... 4044 4096 10/[5]SummaryInformation

1995-07-05 17:25:19 D.... 10/_VBA_PROJECT

..... 9425 9728 10/_VBA_PROJECT/812f9922c6

..... 12302 12800 10/_VBA_PROJECT/7b2f9922a4

..... 36937 37376 10/_VBA_PROJECT/dir

..... 6609 6656 10/_VBA_PROJECT/7e2f9922b5

..... 23014 23040 10/_VBA_PROJECT/872f9922e8

..... 7995 8192 10/_VBA_PROJECT/842f9922d9

..... 5338 5632 10/_VBA_PROJECT/902f992333

..... 36119 36352 10/_VBA_PROJECT/8d2f99231e

..... 18129 18432 10/_VBA_PROJECT/932f992342

..... 13055 13312 10/_VBA_PROJECT/b42fbcaa59

..... 208 256 10/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

..... 4228 4608 [5]SummaryInformation

..... 956 960 [5]DocumentSummaryInformation

..... 106 128 9/[1]CompObj

..... 20 64 9/[1]Ole

..... 5914 6144 9/WordDocument

..... 0 0 9/[3]View000

..... 1520 1536 9/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 220 256 9/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

..... 16141 16384 7/Book

..... 20 64 7/[1]Ole

..... 0 0 7/[3]View000

..... 102 128 7/[1]CompObj

..... 188 192 7/[5]SummaryInformation

..... 192 192 7/[5]DocumentSummaryInformation

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

1995-07-05 17:25:19 345316 351168 55 files, 8 folders

Sure enough, the OBZ file has a Visual Basic macro (VBA_Project). Unfortunately, it appears to be nested in an additional folder within the container, with a variable number number which is likely to change from file to file. That fact will make identification in PRONOM much more difficult, as the signatures are not designed for variable names. Possibly something we can investigate later.

Microsoft Binder was only released in Office 95, 97, and 2000, but was supported in Office XP and 2003 through an UNBIND.EXE application which would simply separate all the different objects back out to the individual files.

The Microsoft Office Binder is not included in Office 2003. However, if a Binder file created in a previous version of Office contains information you want to access, you can use the Unbind tool to pull out the information and save it in the formats of the appropriate programs. In order to do this procedure, the Unbind tool must be installed.

As always, you can look at some sample files and my proposal for updated signatures on my GitHub page.