Years ago I bought my first digital camera. It was an Epson PhotoPC 3100z and I bought it because it could capture a digital image directly to a TIFF file. I don’t think most people would care about such a feature, but I thought it was awesome. Granted it filled up the small 32MB compact flash card pretty quick, I had to upgrade to a 512MB card, that set me back.

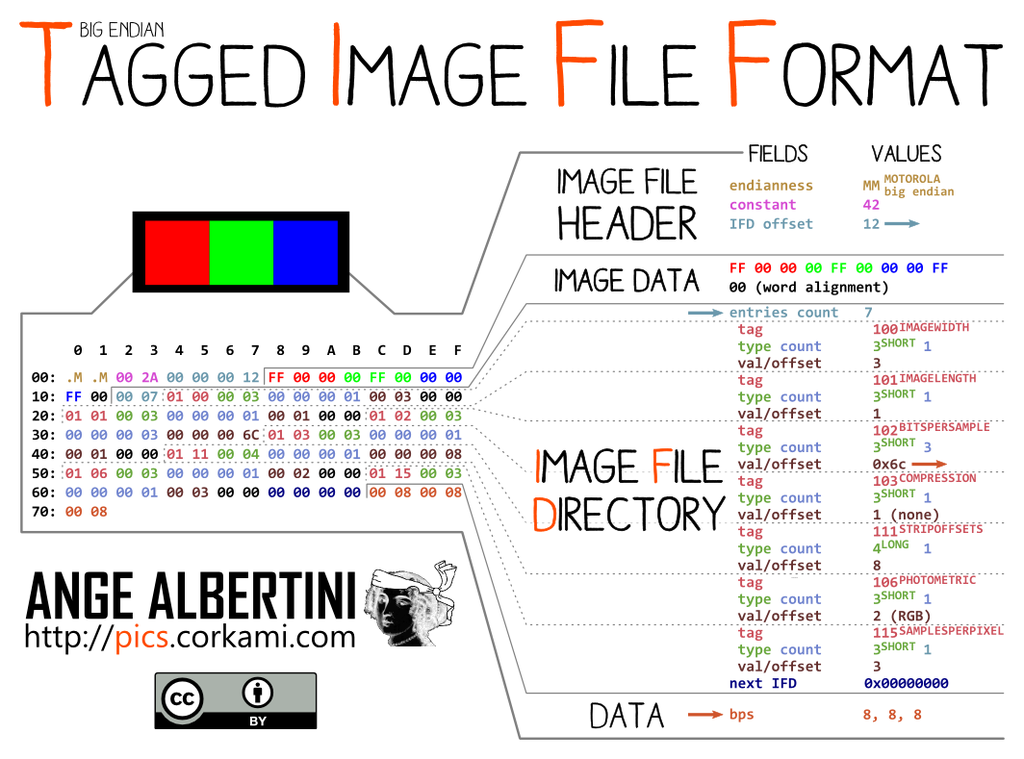

TIFF images are pretty universal, they have a well known structure and have been around for a very long time. I have written about TIFF’s before, so I wont go into too much about the format. The format is well respected in the preservation community, although one of the best websites, Aware Systems, documenting the various TIFF tags has gone dark in the this year, here is an archived version.

Many of the digital camera’s from the beginning to now use the TIFF format to store RAW sensor data. Most use their own extension and follow well established methods for storing the sensor data in an IFD with lots of common and custom tags. The DNG format is an open RAW format which uses the TIFF format to store sensor data, although many use SubIFD’s and can be incompatible with some software.

The first Digital Camera was invented by a Kodak employee, Steve Sasson in 1975, well, he was the first to use a CCD sensor in a self contained unit. This led Kodak to push the technology forward and in 1991 released the Kodak DCS digital system which used Nikon cameras equipped with a digital sensor. These early digital cameras were quite expensive, they used early CF cards and SCSI connections. Kodak released a few models of the DCS series, first on Nikon bodies, then on some Canon bodies. These early cameras used the TIFF format to store the RAW sensor data. For some reason, they decided to use a proprietary method and compression while still using the TIF extension.

Kodak was responsible for many new image file formats. Not sure why they decided to use a common format like TIFF and still use the TIF extension, but make it proprietary. The RAW file created by the DCS series of camera’s had to be opened with special plugins or software, if you tried to open the TIFF’s with anything else, you would only see the small thumbnail image located at IFD0 instead of the full size image hidden in a SubIFD1.

Finding samples of this format is particularly hard as they have the common TIF extension. The camera’s are also pretty rare and finding one is difficult, especially in working condition. I was only aware of a couple samples on the rawsamples.ch site, but that wasn’t enough to understand the format as the two files had a different structure.

hexdump -C RAW_KODAK_DCS460D_FILEVERSION_3.TIF | head

00000000 49 49 2a 00 00 03 00 00 7c 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 |II*.....|.......|

00000010 4b 4f 44 41 4b 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 |KODAK |

00000020 44 43 53 34 36 30 44 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 |DCS460D |

00000030 46 49 4c 45 20 56 45 52 53 49 4f 4e 20 33 20 20 |FILE VERSION 3 |

00000040 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000050 30 35 31 39 39 38 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 |051998 |

00000060 34 36 30 2d 32 39 35 30 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |460-2950........|

00000070 31 39 39 30 3a 30 31 3a 30 31 20 31 32 3a 30 32 |1990:01:01 12:02|

00000080 3a 30 37 00 5b 20 32 5d 0d 49 53 4f 3a 20 20 20 |:07.[ 2].ISO: |

00000090 20 20 20 20 20 38 30 20 20 0d 41 70 65 72 74 75 | 80 .Apertu|

hexdump -C RAW_KODAK_DCS560C.TIF | head

00000000 4d 4d 00 2a 00 00 11 76 00 04 f7 50 00 00 00 00 |MM.*...v...P....|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00000040 54 68 69 73 20 69 6d 61 67 65 20 66 69 6c 65 20 |This image file |

00000050 77 61 73 20 63 72 65 61 74 65 64 20 62 79 20 61 |was created by a|

00000060 20 4b 6f 64 61 6b 20 44 43 53 35 36 30 43 20 64 | Kodak DCS560C d|

00000070 69 67 69 74 61 6c 20 63 61 6d 65 72 61 2e 20 28 |igital camera. (|

00000080 6e 75 6c 6c 29 20 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |null) .........|

00000090 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

There is/was a website called https://raw.pixls.us/, but it has been offline since last June, the regular site still works, but the raw sub-domain is unreachable. Luckily the wayback machine had archived a few samples.

I also found a reference on an older website referring to a sample set maintained by Kodak for developers using the SDK, but also no longer available. You can find the old website also on the wayback machine.

With a few more samples to refer to, it makes it easier to understand the headers and put together a signature. There was an SDK, but seems to be difficult to locate today, but the manual does give us a little more info on the different models and their format.

So from the SDK statement, the samples I have in TIF, and others I have in the more recent DCR format, I can conclude the custom TIF format was used with the DCS 3xx, 4xx, 5xx, 6xx models and from 7xx on the DCR format was used as the camera RAW. Looking closer at the samples in TIF, we can see all the 4xx models used the “FILE VERSION 3” version of the format, while the others have the full statement in the header. Not 100% clear on which format came first, but the 4xx models are some of the earliest models.

At the time, there was only Kodak software that could properly “develop” the RAW file taken by these camera models. Today that has changed and the format has been added to many open source libraries such as libraw and rawspeed. Many other commercial products also claim to support the DCS models including Adobe Camera Raw, which seems to be able to open these TIF’s.

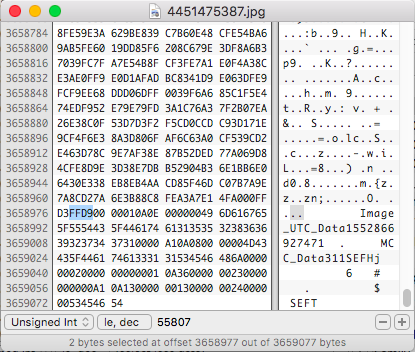

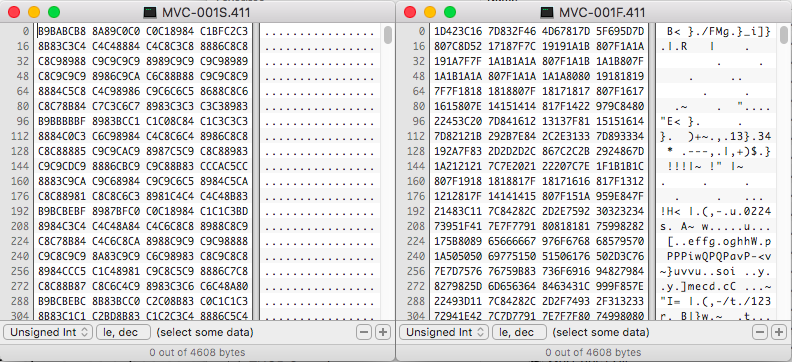

Distinguishing these RAW TIF’s is important to properly manage them over the long term. These images currently identify in the PRONOM repository as regular TIF’s, fmt/353, so we would need to create a signature which identifies the standard TIFF header, but also uses bytes unique to this format. In the few samples I have the “VERSION 3” images all start with the litte-endian header, “49492A00”, while the other samples start with the big-endian header, “4D4D002A”. That makes it a little easier for each signature.

For for the “VERSION 3” format we could use a pattern such as 49492A00{12}4B4F44414B{11}(444353|454F53444353). This looks for the TIFF header, skips 12 bytes, looks for the word “KODAK”, skips 11 more bytes to then look for either “DCS” or “EOSDCS” right before the camera model number.

For the other format we also look for the TIFF header, but then find the whole string used in all the samples. 4D4D002A{60}5468697320696D6167652066696C652077617320637265617465642062792061204B6F64616B20444353{5}6469676974616C2063616D6572612E

This looks for the big-endian header, then the string, “This image file was created by a Kodak DCS”, skipping the model number, then the end of the string, “digital camera.” This should catch all the different models of this format.

You can find my proposed signature on my GitHub page, since none of the samples belong to me, you can find them above in some of the links.