When it comes to Digital Preservation, the easiest types of file formats to preserve are often single self contained formats with lots of documentation. There are plenty of formats which break this norm, but a file format like a simple TIFF file is well understood and can stand on its own. The hardest file formats to preserve, I have found, are the complex under documented formats which often show up when you don’t expect them. There is a file format type which indeed makes things difficult. The project format.

There are many software tools out there which generate a “Project”, this is often proprietary and can only be used by the software which created it. Project files are also interdependent, meaning they require other files in known locations in order to be used. This interdependence is often links to images, audio, video, fonts, and other multimedia. The file format itself is just a reference to all the project settings and the paths to the files included in the project. This makes things very difficult to preserve and maintain the complex structure required. Any renaming, removing, or moving the files out of their original order can render the project useless. Many project formats are human readable in XML, or other human readable text, but others are not. I have made a recent attempt to document more Project formats on the File Format Wiki, including many Label and Optical disc project formats, along with updates to Adobe InDesign, QuarkXPress and other desktop publishing project formats. There is still plenty of work needed in other Video and Audio project formats.

Apple computers over the years has created some very powerful software for content creators to use, especially in Video editing. iMovie was used by many home movie editors and iDVD to burn those movies to DVD to share with family and friends, but Apple also sold a professional Video Editing suite which included Final Cut Pro.

Final Cut Pro started life as a Macromedia software tool called KeyGrip which never was released and later bought by Apple. Final Cut Pro was well used and loved by video editors and was given a major upgrade in 2011 to Final Cut Pro X, which was full re-written to be 64-bit. This change included a change to the Project file format. So for version 1 through version 7, Final Cut Pro used a project format with the extension .FCP. Lets take a closer look at the this project format.

hexdump -C Swing.fcp | head 00000000 a2 4b 65 79 47 0a 0d 0a 00 00 00 00 20 fc c5 5b |.KeyG....... ..[| 00000010 00 de b3 11 d0 93 19 00 05 02 18 66 07 00 00 00 |...........f....| 00000020 03 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 01 00 |................| 00000030 00 00 11 07 73 75 62 74 79 70 65 00 00 00 01 01 |....subtype.....| 00000040 00 00 00 03 00 06 4e 4f 55 4e 44 4f 00 00 00 00 |......NOUNDO....| 00000050 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 07 52 55 |..............RU| 00000060 4e 54 49 4d 45 00 00 00 00 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 |NTIME...........| 00000070 00 00 00 01 07 76 69 65 77 65 72 73 00 00 00 00 |.....viewers....| 00000080 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 08 |................| 00000090 63 68 69 6c 64 72 65 6e 00 00 00 00 01 01 00 00 |children........| * 00000e30 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 07 8c |................| 00000e40 b3 2e 56 40 4d 6f 6f 56 54 56 4f 44 00 02 00 02 |..V@MooVTVOD....| 00000e50 00 00 00 11 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 00000e60 00 00 00 0b 44 61 6e 63 65 20 53 68 6f 74 73 00 |....Dance Shots.| 00000e70 00 01 00 08 00 00 07 8a 00 00 07 84 00 02 00 2f |.............../| 00000e80 41 54 54 4f 20 52 41 49 44 30 20 47 72 6f 75 70 |ATTO RAID0 Group| 00000e90 3a 54 55 54 4f 52 49 41 4c 3a 44 61 6e 63 65 20 |:TUTORIAL:Dance | 00000ea0 53 68 6f 74 73 3a 49 6e 74 72 6f 2e 6d 6f 76 00 |Shots:Intro.mov.| 00000eb0 00 09 00 a8 00 a8 61 66 70 6d 00 00 00 00 00 03 |......afpm......| 00000ec0 00 18 00 39 00 59 00 75 00 95 00 9e 07 49 4c 31 |...9.Y.u.....IL1| 00000ed0 20 33 72 64 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 | 3rd............| 00000ee0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0f 77 61 |..............wa| 00000ef0 6c 74 d5 73 20 43 6f 6d 70 75 74 65 72 00 00 00 |lt.s Computer...| 00000f00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 41 54 |..............AT| 00000f10 54 4f 20 52 41 49 44 30 20 47 72 6f 75 70 00 00 |TO RAID0 Group..| 00000f20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 07 77 73 68 69 72 65 |..........wshire| 00000f30 73 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |s...............| 00000f40 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 00000f50 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ff ff 00 00 |................| 00000f60 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 41 54 54 4f 20 52 41 49 |........ATTO RAI| 00000f70 44 30 20 47 72 6f 75 70 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 2b |D0 Group.......+| 00000f80 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 03 54 55 54 4f |............TUTO| 00000f90 52 49 41 4c 00 44 61 6e 63 65 20 53 68 6f 74 73 |RIAL.Dance Shots| 00000fa0 00 49 6e 74 72 6f 2e 6d 6f 76 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.Intro.mov......|

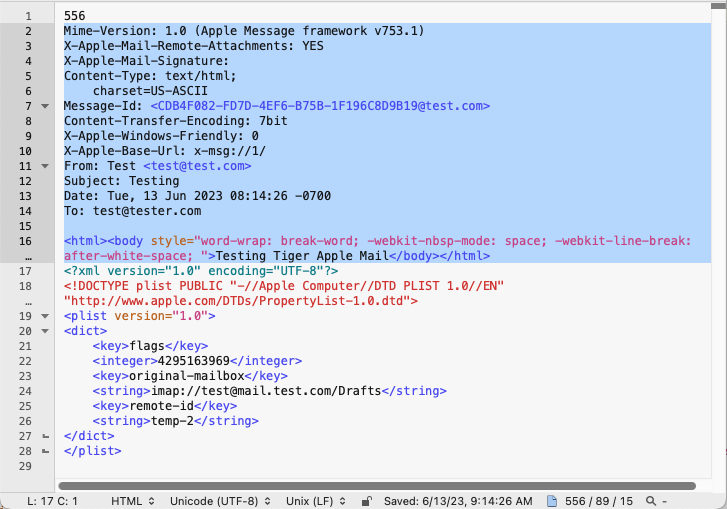

From the header we can see a remnant of the original KeyGrip software, but later in the file we find some references to files in the Mac HFS path format which includes a colon instead of a slash. These are the paths to the each of the MOV files used in the Project. This file is from the tutorial disk of Final Cut Pro version 1.2, so lets take a look at the last version released, version 7.

hexdump -C Lesson 1 Project.fcp | head 00000000 a2 4b 65 79 47 0a 0d 0a 01 de 00 00 00 20 08 92 |.KeyG........ ..| 00000010 66 c4 28 d7 11 8a e5 00 30 65 ec fe 98 03 00 00 |f.(.....0e......| 00000020 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 00 01 15 |................| 00000030 00 00 00 07 73 75 62 74 79 70 65 01 00 00 00 01 |....subtype.....| 00000040 03 00 00 00 00 06 4e 4f 55 4e 44 4f 00 00 00 00 |......NOUNDO....| 00000050 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 07 52 55 |..............RU| 00000060 4e 54 49 4d 45 00 00 00 00 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 |NTIME...........| 00000070 01 00 00 00 07 76 69 65 77 65 72 73 00 00 00 00 |.....viewers....| 00000080 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 08 |................| 00000090 63 68 69 6c 64 72 65 6e 00 00 00 00 01 01 01 00 |children........|

Almost identical to the first version, which is helpful for identification, but if we need to identify based on version, it might prove a little more difficult. It appears all the samples I have and have seen reference to all begin with the same 5 hex values, A24B657947, 0xA2 KeyG. It’s hard to know what other hex values might have something to do with versions of the file format. More samples could tell us, but from what I have the 20 bytes starting from offset 12 seems to be consistent among the different version samples. But for now the 5 bytes at the beginning of the file should suffice for identification.

When Final Cut Pro went through a complete re-write in 2011, the FCP format was abandoned. Not only made obsolete, but completely unsupported. The new Final Cut Pro X software was not able to support this now obsolete format. The new format followed the pattern of many other Apple formats of using a folder identified through an extension as a single file. Called a bundle format, Final Cut Pro X used the extension, .FCPBUNDLE. This bundle could include the media assets along with project settings/thumbnails and clips. Because of this “bundle” format, identification would have to be done at the individual file level inside the bundle. This would include formats with extensions such as .flexolibrary and .fcpevent, which appear to be SQLite databases. This complex format makes preservation of this type of object difficult with current methods and practices.

Luckily Apple didn’t leave Final Cut Pro users completely unable to migrate their content. Final Cut Pro could export the project as an XML file. This format is called Final Cut Pro XML Interchange Format and was well documented. The format was not made to bridge the gap from Final Cut Pro to Final Cut Pro X, but rather make the project file more useful outside of Final Cut Pro. Final Cut Pro X actually can’t open these files either, which is why a third party developer came in and developed 7toX (SendtoX) to allow for projects to be converted to a newer XML format.

Lets take a look at the basic Final Cut Pro XML Interchange Format which has a standard XML extension:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE xmeml> <xmeml version="5"> <sequence id="Sequence 1 ">...</sequence> </xmeml>

Standard XML with a Doctype/root of xmeml. Clever. A little ways into the XML we also see:

<appspecificdata> <appname>Final Cut Pro</appname> <appmanufacturer>Apple Inc.</appmanufacturer> <appversion>7.0</appversion> </appspecificdata>

Final Cut Pro X also has an XML format which is different than XMEML and has an extension FCPXML:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE fcpxml>

<fcpxml version="1.8">

<resources>

<format id="r1" name="FFVideoFormatDV720x480i5994" frameDuration="2002/60000s" fieldOrder="lower first" width="720" height="480" paspH="10" paspV="11" colorSpace="6-1-6 (Rec. 601 (NTSC))"/>

</resources>

<library location="file:///Untitled.fcpbundle/">...</library>

</fcpxml>

A different Doctype/root and structure but should be easy to identify.

The preservation of projects files, according to some, is not necessary since they are not the finalized product. Preserving the finalized output would be preferable as it can be managed easier and represent the final render of a project. But identification of the Final Cut Pro project and all the assets gives the option to access a collection more accurately. I was able to create a signature for the FCP, XML, and FCPXML formats. Take a look on my GitHub for the signatures and some test files.