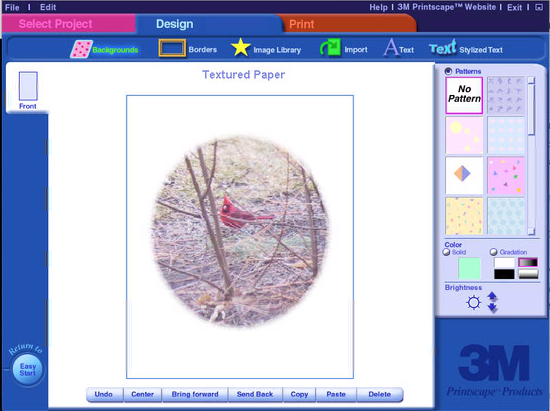

Lets talk TIFF, or Tagged Image File Format. It is well documented and accepted by the community. The format has been around since 1986, first developed by Aldus as a image format for scanners. The TIFF format is now used worldwide as a preferred format for scanning and preservation of cultural heritage objects.

As amazing as the format is, there are a few features of the format which can be a preservation risk. I want to focus on three of those risks.

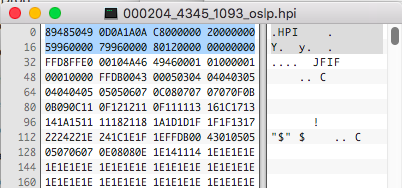

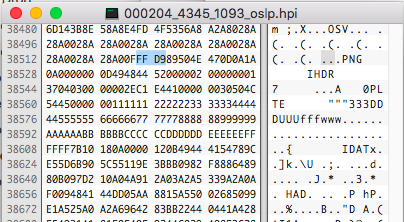

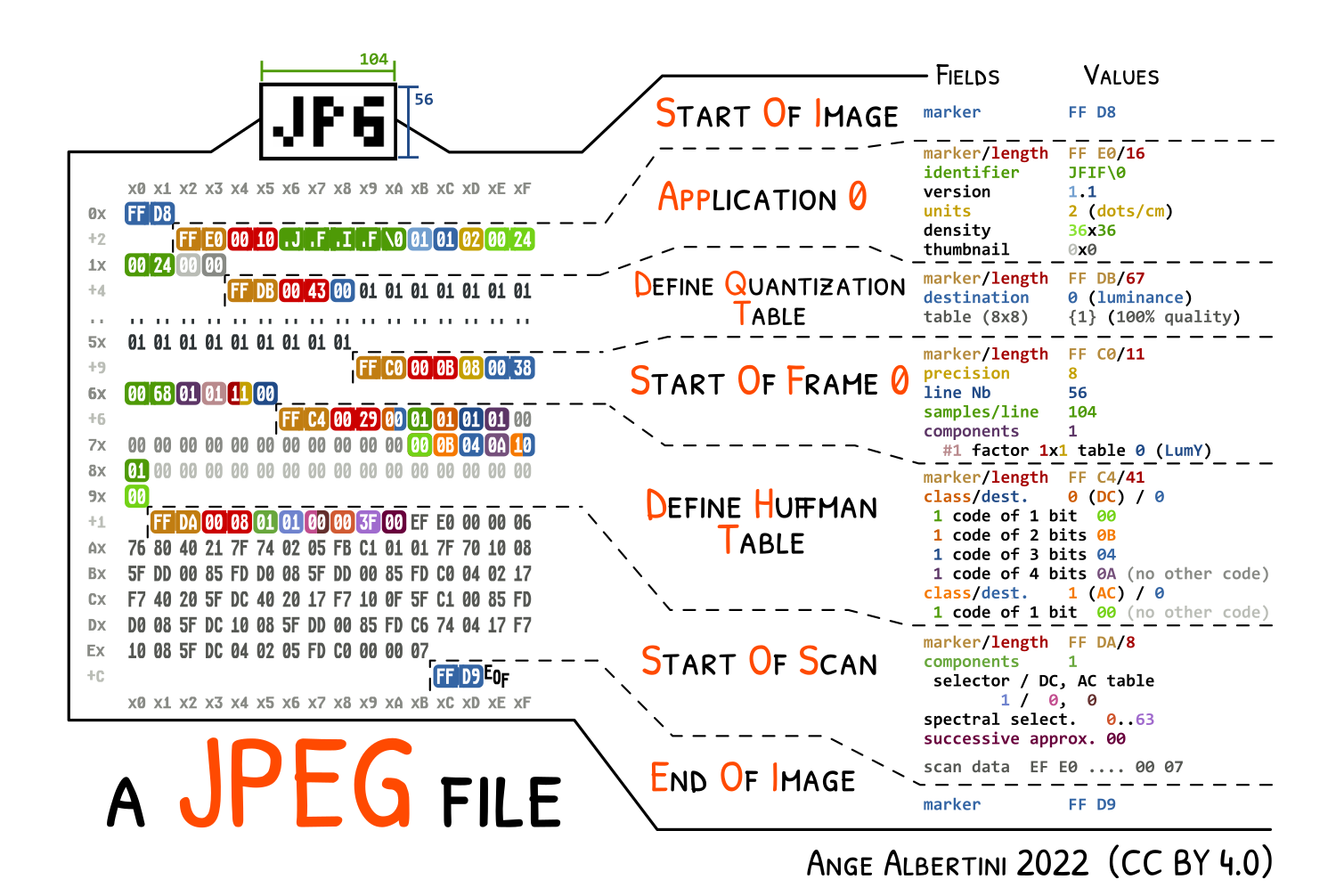

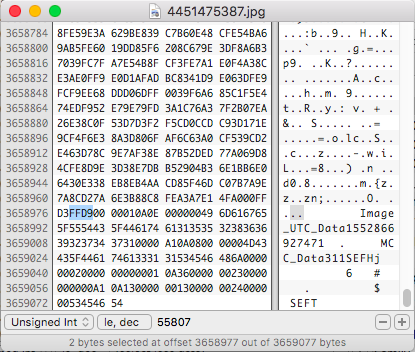

The Tagged Image File Format has a well known header:

A TIFF file begins with an 8-byte image file header, containing the following information: Bytes 0-1: The byte order used within the file. Legal values are: “II” (4949.H) LSB (IBM) “MM” (4D4D.H) MSB (Mac) Bytes 2-3 An arbitrary but carefully chosen number (42). Bytes 4-7 The offset (in bytes) of the first IFD.

Putting this poster of the TIFF structure in your office will impress your co-workers, guaranteed. Thanks Ange!

The three risks I have been pondering lately are:

- Multiple IFD’s

- Metadata

- DNG format

TIFF version 6.0 was released in 1992 and is the most recent version. Although some vendors are free to add their own private tags. In 1995 Adobe added an addendum which added some additions for use with PageMaker.

One of the main features of the TIFF format is its ability to hold multiple pages. In Adobe’s words:

TIFF has always supported what amounts to a singly linked list of IFD’s in a single TIFF file, via the “next IFD pointer,” though most applications currently ignore any IFD beyond the first one. Probably the best use for a linked list of IFD’s is when you want to store multiple different but related images in the same file—a ‘burst’ of images from a camera, for example.

Adobe PageMaker® 6.0 TIFF Technical Notes

Take note of the highlighted text, software like Adobe Photoshop will ignore any IFD beyond the first one. Even worse, Photoshop won’t even mention there are additional IFD’s. I have used many document scanners which default to multipage TIFF capture and have lost pages because of this. Because of this I have always built my workflows around single page TIFF’s for all scanning and we check against this as a rule.

What also makes this hard is how some capture software uses additional IFD’s. CaptureOne is a popular imaging software used by photographers and cultural heritage institutions. We have used it to connect to our PhaseOne cameras for capture of books and other flat objects. By default the software exports the final TIFF image with a thumbnail.

With the “No Thumbnail” unchecked we get this TIFF structure:

identify _MG_0193.tif _MG_0193.tif[0] TIFF 3456x5184 3456x5184+0+0 8-bit sRGB 51.3136MiB 0.030u 0:00.026 _MG_0193.tif[1] TIFF 107x160 107x160+0+0 8-bit sRGB 0.000u 0:00.007 <IFD0:ImageWidth>3456</IFD0:ImageWidth> <IFD0:ImageHeight>5184</IFD0:ImageHeight> <IFD1:SubfileType>Reduced-resolution image</IFD1:SubfileType> <IFD1:ImageWidth>107</IFD1:ImageWidth> <IFD1:ImageHeight>160</IFD1:ImageHeight> <IFD1:BitsPerSample>8 8 8</IFD1:BitsPerSample>

So Imagemagick identifies two pages 0 and 1 with the second a much smaller resolution than the first. Exiftool reports back IFD0 and IFD1 with IFD1 having a SubfileType of a Reduced-resolution image. Makes sense, it is a thumbnail. In looking at the specifications for TIFF 6.0, I can find no mention of the word “thumbnail”, but the specification does make mention of “reduced resolution” images:

If multiple subfiles are written, the first one must be the full-resolution image. Subsequent images, such as reduced-resolution images, may be in any order in the TIFF file.

The specification also gives us this warning:

TIFF readers must be prepared for multiple images (subfiles) per TIFF file, although they are not required to do anything with images after the first one.

Scary to think about how a reader is not required to do anything, not even warn against multiple IFD’s (Subfiles).

The EXIF specifications seem to expand on this through attributes:

Attribute information can be recorded in 2 IFDs (0th IFD, 1st IFD) following the TIFF structure, including the File Header. The 0th IFD records compressed image attributes (the image itself). The 1st IFD may be used for thumbnail images.

Page 97 of EXIF Specification

Take a look at the information and Figure 6 on page 21-22 in the EXIF specification.

Adobe early on decided to use their own tags for thumbnail data. Since Photoshop 5, Adobe has stored the thumbnail in Tag 1036.

1036 Photoshop Thumbnail : (Binary data 4625 bytes, use -b option to extract)

There is another TIFF structure sometimes used in older FAX compressed multipage TIFFs and now used in the DNG Specification. The SubIFD tag was writable using the libtiff “thumbnail” tool, but is now depreciated. Originally described in the TIFF/EP specification, DNG files use SubIFD trees.

DNG files are often talked about in the same way TIFF files are, and many tools handle both seamlessly. One of the major differences is that DNG files switch their IFD use. IFD0 is often the reduced-resolution thumbnail and SubIFD the full-resolution image.

<IFD0:SubfileType>Reduced-resolution image</IFD0:SubfileType> <IFD0:ImageWidth>256</IFD0:ImageWidth> <IFD0:ImageHeight>171</IFD0:ImageHeight> <SubIFD:SubfileType>Full-resolution image</SubIFD:SubfileType> <SubIFD:ImageWidth>3516</SubIFD:ImageWidth> <SubIFD:ImageHeight>2328</SubIFD:ImageHeight>

This can cause issues when trying to extract technical metadata from images, knowing which IFD to get the main image details requires a bit of work. I’ll save DNG for another blog post.

TIFF Metadata is a vital part of preservation. The metadata can provide technical properties of the file along with some descriptive information. It amazes me how much the embedded metadata can vary from a scanner or camera capture device. The digitization lab I worked in for years had scanners from Epson, Fujitu, Canon and others. Along with cameras made by Canon, PhaseOne, and Copibooks. Each one with a vastly different set of metadata using different standards. Even when each workflow produced final uncompressed TIFF images, they all varied in metadata.

The TIFF images with the leasT amount of metadata was from the Epson scanners. When using the free Epson Scan software, not a single metadata field was embedded, no dates, scanner model or manufacturer. More was embedded when you used the Silverfast professional software included with each Epson, but even then if you didn’t add any IPTC fields, the metadata was limited.

The most metadata came from the camera systems, especially the PhaseOne/CaptureOne systems. Even though it produced the most and had valuable properties, there were some issues. I already discussed the thumbnail issue, but PhaseOne decided they wanted to change how some of the tags were used.

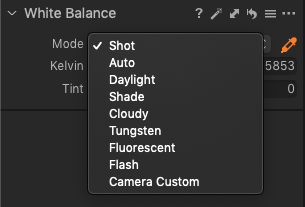

CaptureOne has quite the list of white balance options. Which is great for the photographer, but not so great for adhering to the TIFF standard.

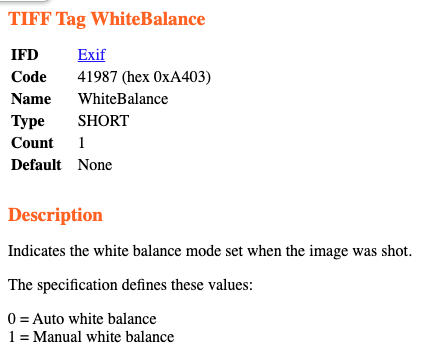

According to the EXIF TIFF Specification, there are only two values allowed for White Balance, Auto or Manual. A CaptureOne produced TIFF will have this value if Auto or Manual are not chosen:

41987 White Balance : Unknown (5) 37384 Light Source : Other

The different lighting situations should be identified using the “Light Source” 37384 tag, but alas they chose to add to white balance instead. When I asked about this, they responded that they requested this update to the TIFF spec, but they weren’t willing so they took matters into their own hands. You can read the conversation on the JHOVE issues page.

The TIFF format is very accepted in the Cultural Heritage community as a preferred preservation format. The specification is well understood and documented. I just hope we can continue to openly discuss issues that arise in preservation which add risk to our collections. Some issues are minor compared to others. Sometimes it’s the tools we use to validate formats like TIFF which are wrong and need to be corrected. The talk more about these issues and how to manage them.