Is there a perfect raster image format? TIFF has been around quite some time and is generally accepted as a preferred preservation format. There have been a few attempts to have a single file contain multiple resolutions with the purpose of providing resolutions for different uses, lower-resolution for web and higher-resolution for print. Even the semi popular JPEG2000 added multiple resolutions to improve the JPEG format. Kodak came up with a few ideas to do this as well. The Kodak PCD, PhotoCD or Image PAC files was one that was used for awhile before it was abandoned. Another was FlashPix.

I briefly mentioned FlashPix on an earlier post about the Microsoft Picture It! format. They are extremely similar. Both. have the same basic structure in a Compound Object format. Some of the FlashPix files generated by Picture It! even have the same identifiers in the CompObj header.

FlashPix was supposed to be the answer to all the problems with storing bitmap image data and how we view the web. Kodak partnered with some big names, Microsoft Corporation, Hewlett-Packard Company and Live Picture, Inc, were among them. Kodak marketed the format and even included it as a native file format to some of its new digital cameras. The format was made official in June of 1996, with a Whitepaper explaining all the benefits and architecture. There was a lot of hype, some even calling it, “Not your Grandma’s format“. Many graphics software started to include support for the new format, including Adobe Photoshop. So what happened, why didn’t the format catch on? Some say it was the size of storing multiple resolutions in one file, others believe it was the complicated Compound Object structure that lead to its demise. Either way, the format had a lot of hype in the late 1990’s, but by the year 2000, it had gone silent and all the websites went away.

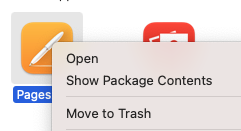

FlashPix did have a big impact, and there were many software and hardware devices which were made compatible. There are a few stories left behind of those who scanned all their photos to the FlashPix format only to find a few years later it was unsupported on more modern computers. There was also a few early digital camera’s which could capture directly to the format. Take my Kodak DC260 zoom camera, circa 1998. Changing the Capture Preferences, I can switch between a JPG and FPX.

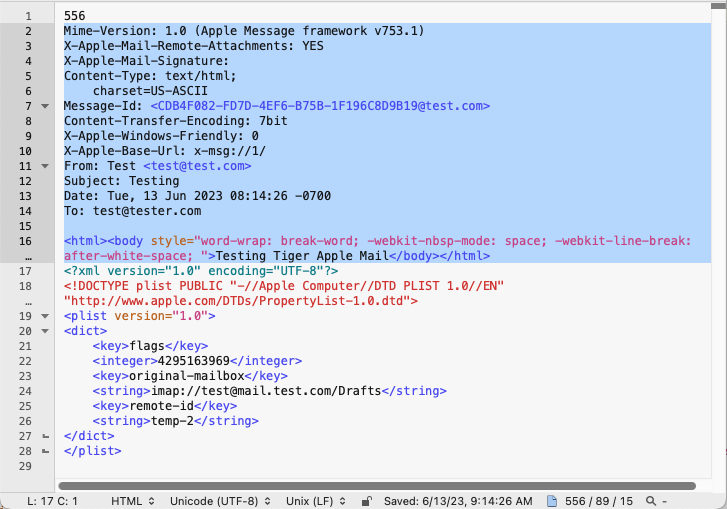

Using exiftool we can take a look at one of the images from the camera:

exiftool P0004795.FPX ExifTool Version Number : 12.73 File Name : P0004795.FPX Directory : GitHub/digicam_corpus/Kodak/DC260/DC260_01 File Size : 251 kB File Modification Date/Time : 2024:01:06 12:54:20-07:00 File Access Date/Time : 2024:01:06 13:20:46-07:00 File Inode Change Date/Time : 2024:01:06 13:04:34-07:00 File Permissions : -rwxrwxrwx File Type : FPX File Type Extension : fpx MIME Type : image/vnd.fpx Code Page : Unicode UTF-16, little endian Data Object ID : 13BC5A58-6B90-1B6B-12C9-0800201177F8 Data Object Status : Exists, Not Purgeable Creating Transform : Source Image Using Transforms : Cached Image Height : 1024 Cached Image Width : 1536 Comp Obj User Type Len : 16 Comp Obj User Type : FlashPix_Object Visible Outputs : 1 Maximum Image Index : 1 Maximum Transform Index : 0 Maximum Operation Index : 0 Thumbnail Clip : (Binary data 18480 bytes, use -b option to extract) Revision Number : 1 Create Date : 2024:01:06 12:53:29 Modify Date : 2024:01:06 12:53:29 Software : KODAK DIGITAL SCIENCE DC260 Image Width : 1536 Image Height : 1024 Subimage Width : 1536 Subimage Height : 1024 Subimage Color : RGB Subimage Numerical Format : 8-bit, Unsigned Decimation Method : None (Full-sized Image) JPEG Tables : (Binary data 558 bytes, use -b option to extract) Number Of Resolutions : 1 Max JPEG Table Index : 1 Scene Type : Original Scene Software Release : KODAK DIGITAL SCIENCE DC260 Make : Eastman Kodak Company Camera Model Name : KODAK DIGITAL SCIENCE DC260 Serial Number : 7577 Exposure Time : 1/180 F Number : 4.7 Exposure Program : Program AE Exposure Compensation : 0 Subject Distance : 0.520 m Metering Mode : Center-weighted average Light Source : Unknown Focal Length : 24.0 mm Max Aperture Value : 4.6 Flash : No Flash Exposure Index : 90 Sharpness Approximation : 0 File Source : Digital Camera Sensing Method : One-chip color area Extension Create Date : 2024:01:06 12:53:29 Extension Modify Date : 2024:01:06 12:53:29 Creating Application : Picoss Extension Name : ijuhsimasa Extension Persistence : Always Valid Extension Description : Data Object Store 000001 Storage-Stream Pathname : /Data Object Store 000001 Extension Class ID : 56616000-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B Used Extension Numbers : 1 Screen Nail : (Binary data 4304 bytes, use -b option to extract) Subimage Tile Count : 384 Subimage Tile Width : 64 Subimage Tile Height : 64 Num Channels : 3 Audio Stream : (Binary data 30780 bytes, use -b option to extract) Aperture : 4.7 Image Size : 1536x1024 Megapixels : 1.6 Shutter Speed : 1/180 Preview Image : (Binary data 4164 bytes, use -b option to extract) Focal Length : 24.0 mm

The file also does identify in PRONOM:

sf P0004795.FPX

---

siegfried : 1.11.0

scandate : 2024-01-17T23:13:59-07:00

signature : default.sig

created : 2023-12-17T15:54:41+01:00

identifiers :

- name : 'pronom'

details : 'DROID_SignatureFile_V116.xml; container-signature-20231127.xml'

---

filename : 'P0004795.FPX'

filesize : 250880

modified : 2024-01-06T12:54:20-07:00

errors :

matches :

- ns : 'pronom'

id : 'x-fmt/56'

format : 'Kodak FlashPix Image'

version :

mime : 'image/vnd.fpx'

class : 'Image (Raster)'

basis : 'extension match fpx; container name CompObj with byte match at 53, 36 (signature 2/2)'

warning :

If you notice, PRONOM has two signatures for the FlashPix format, this image was identified with signature #2. The first signature looks for the string “FlashPix Object”, but the second looks for the CLSID which is unique to each compound object format. FlashPix has the CLSID: {56616700-c154-11ce-8553-00aa00a1f95b}. Looking at many of the other samples I have there is much variation on the use of the string and CLSID.

FlashPix samples:

FlashPix Object({56616000-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B}

FlashPix Object({56616800-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B}

Picture It! FlashPix'{56616700-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B}

LPI FlashPix'{56616700-c154-11ce-8553-00aa00a1f95b}

FlashPix_Object'{56616700-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B}

'{56616700-C154-11CE-8553-00AA00A1F95B}

Picture It!'{56616700-c154-11ce-8553-00aa00a1f95b}

Flashpix Toolkit Application'{56616700-c154-11ce-0000-000000000000}

The images from the Kodak Camera use “FlashPix_Object” string so with the underscore it doesn’t match the first signature, but others I made using Picture It! software used a couple variations. Many don’t use the string at all. Others use a sightly different CLSID in both uppercase and lowercase. We will have to suggest adjustments to the current signature to identify them all.

Looking at the contents of the OLE container we can see some interesting things.

Path = P0004795.FPX

Type = Compound

Physical Size = 250880

Extension = compound

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Size Compressed Name

------------ ------------ ------------------------

188 192 [5]Data Object 000001

272 320 [1]CompObj

388 448 [5]Extension List

144 192 [5]Global Info

Data Object Store 000001

18704 18944 [5]SummaryInformation

816 832 Data Object Store 000001/[5]Image Contents

272 320 Data Object Store 000001/[1]CompObj

988 1024 Data Object Store 000001/[5]Extension List

1624 1664 Data Object Store 000001/[5]Image Info

4332 4608 Data Object Store 000001/[5]Screen Nail_bd0100609719a180

Data Object Store 000001/Resolution 0005

Data Object Store 000001/Audio_bd0100609719a180

1112 1152 Data Object Store 000001/[5]KDC_bd0100609719a180

72 128 Data Object Store 000001/[5]SummaryInformation

108 128 Data Object Store 000001/Audio_bd0100609719a180/[5]Audio Info

30808 31232 Data Object Store 000001/Audio_bd0100609719a180/Audio Stream 000000

6208 6656 Data Object Store 000001/Resolution 0005/Subimage 0000 Header

176378 176640 Data Object Store 000001/Resolution 0005/Subimage 0000 Data

------------ ------------ ------------------------

242414 244480 16 files, 3 folders

The main CompObj is where we find the identification information, but the Data Object Store 000001 directory is where all the image data is stored. In a multiple resolution image we might see additional Resolution directories. You may also notice a mention of an Audio directory. Yes, this image was captured and then audio was recorded with it. Not a video, but an audio clip associated with the image. FlashPix can contain audio streams. This isn’t the first time we have seen this, HP camera’s also have this function which as it turns out is stored in a FlashPix exif extension within a JPEG.

The FlashPix native format may have disappeared, but the format lives on as an extension to Exif data, allowing you to embed audio and other media within a JPEG file. The code for FlashPix was given to ImageMagick and is maintained by them.