Usually in the software world file formats are fairly efficient, the structure is meant to provide a way to store the data of the software being used. There isn’t much need to add additional unnecessary additions. This isn’t always true, but in the early days, disk space was expensive so compression and efficiency ruled. There also wasn’t much need to hide anything or complicate things. That is unless it is intended. This makes me think of two things, Polyglots and Steganography.

Steganography is the art of embedding data within an image. With digital images you can hide another image within the main image by using the most and least significant bits. Fun use of technology, but not something you normally would find in your regular desktop software.

Ange is the master at polyglots. If you haven’t watched his presentation on funky file formats, you are missing out.

Imagine my surprise when I was researching the Picture It! software and the MIX file format only to discover Microsoft decided to make their own polyglot of sorts for their PNG Plus format which replaced the MIX format, then both obsolete when Digital Image was discontinued in 2007. The PNG Plus format was the native format for the Microsoft Picture It! and Digital Image software often found with the Microsoft Works or Digital Imaging suite of software.

According to the help within Digital Image:

The PNG Plus format uses the standard PNG extension but provides saving of layers and pages within the PNG format. Since the PNG format cannot do this natively, how did Microsoft accomplish this? Well, by throwing an OLE container into the middle of the file of course!

PNG Plus files are your regular PNG format and will identify as such. But they are just a low resolution thumbnail of the full image. Let’s take a look:

exiftool PictureIt7-s02.png ExifTool Version Number : 12.70 File Name : PictureIt7-s02.png File Size : 26 kB File Modification Date/Time : 2023:12:26 22:01:58-07:00 File Access Date/Time : 2024:01:01 12:31:07-07:00 File Inode Change Date/Time : 2023:12:26 22:01:58-07:00 File Permissions : -rwx------ File Type : PNG File Type Extension : png MIME Type : image/png Image Width : 500 Image Height : 333 Bit Depth : 8 Color Type : RGB with Alpha Compression : Deflate/Inflate Filter : Adaptive Interlace : Noninterlaced SRGB Rendering : Perceptual Gamma : 2.2 White Point X : 0.3127 White Point Y : 0.329 Red X : 0.64 Red Y : 0.33 Green X : 0.3 Green Y : 0.6 Blue X : 0.15 Blue Y : 0.06 Warning : [minor] Text/EXIF chunk(s) found after PNG IDAT (may be ignored by some readers) Title : PictureIt7-s02 Image Size : 500x333 Megapixels : 0.167

Looks like there is some additional data after the IDAT chunk.

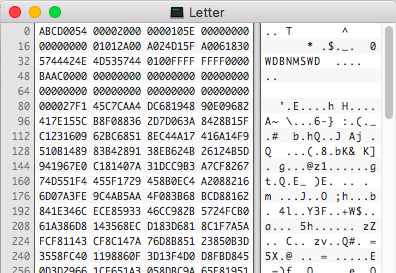

hexdump -C PictureIt7-s02.png | head 00000000 89 50 4e 47 0d 0a 1a 0a 00 00 00 0d 49 48 44 52 |.PNG........IHDR| 00000010 00 00 01 f4 00 00 01 4d 08 06 00 00 00 f6 13 9d |.......M........| 00000020 37 00 00 00 01 73 52 47 42 00 ae ce 1c e9 00 00 |7....sRGB.......| 00000030 00 04 67 41 4d 41 00 00 b1 8f 0b fc 61 05 00 00 |..gAMA......a...| 00000040 00 20 63 48 52 4d 00 00 7a 26 00 00 80 84 00 00 |. cHRM..z&......| 00000050 fa 00 00 00 80 e8 00 00 75 30 00 00 ea 60 00 00 |........u0...`..| 00000060 3a 98 00 00 17 70 9c ba 51 3c 00 00 24 f4 49 44 |:....p..Q<..$.ID| 00000070 41 54 78 5e ed dd 4d a8 15 57 be 28 f0 1e 08 1e |ATx^..M..W.(....| 00000080 e3 47 8e 49 ab c7 d8 81 03 09 41 9c 28 38 e8 80 |.G.I......A.(8..| 00000090 d0 9c 0e 08 0e 1a 11 c2 15 07 5e 5a 07 4d c7 2b |..........^Z.M.+|

The header looks the same as any PNG file, so lets look a little further:

00002560 ff 1f fa 5f 90 66 c9 e6 ad 88 00 00 00 00 63 6d |..._.f........cm| 00002570 4f 44 4e 88 09 c1 00 00 40 00 63 70 49 70 d0 cf |ODN.....@.cpIp..| 00002580 11 e0 a1 b1 1a e1 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 00002590 00 00 00 00 00 00 3e 00 03 00 fe ff 09 00 06 00 |......>.........| 000025a0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 01 00 |................| 000025b0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 10 00 00 02 00 00 00 01 00 |................| * 00002970 ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff 52 00 |..............R.| 00002980 6f 00 6f 00 74 00 20 00 45 00 6e 00 74 00 72 00 |o.o.t. .E.n.t.r.| 00002990 79 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |y...............| 000029a0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 000029b0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 16 00 |................| 000029c0 05 00 ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff 01 00 00 00 7e 7f |..............~.| 000029d0 3f b5 a5 f6 86 43 a1 a1 a3 02 24 d2 88 ef 00 00 |?....C....$.....| 000029e0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 000029f0 00 00 03 00 00 00 40 12 00 00 00 00 00 00 44 00 |......@.......D.| 00002a00 61 00 74 00 61 00 53 00 74 00 6f 00 72 00 65 00 |a.t.a.S.t.o.r.e.| 00002a10 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| * 00003930 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 43 48 |..............CH| 00003940 4e 4b 49 4e 4b 20 04 00 07 00 0c 00 00 03 00 02 |NKINK ..........| 00003950 00 00 00 0a 00 00 f8 01 0c 00 ff ff ff ff 18 00 |................| 00003960 54 45 58 54 00 00 01 00 00 00 54 45 58 54 00 02 |TEXT......TEXT..| 00003970 00 00 22 00 00 00 18 00 46 44 50 50 00 00 43 00 |..".....FDPP..C.| 00003980 4f 00 4e 00 54 00 45 00 4e 00 54 00 53 00 00 00 |O.N.T.E.N.T.S...| 00003990 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| * 000039f0 00 00 1f 00 00 00 00 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 |................| 00003a00 43 00 6f 00 6d 00 70 00 4f 00 62 00 6a 00 00 00 |C.o.m.p.O.b.j...| 00003a10 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| * 00004530 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 |................| 00004540 fe ff 03 0a 00 00 ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| 00004550 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 1a 00 00 00 51 75 |..............Qu| 00004560 69 6c 6c 39 36 20 53 74 6f 72 79 20 47 72 6f 75 |ill96 Story Grou| 00004570 70 20 43 6c 61 73 73 00 ff ff ff ff 01 00 00 00 |p Class.........| 00004580 00 00 00 00 f4 39 b2 71 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.....9.q........| 00004590 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................| * 00006570 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ba 84 |................| 00006580 43 51 00 00 00 18 69 54 58 74 54 69 74 6c 65 00 |CQ....iTXtTitle.| 00006590 00 00 00 00 50 69 63 74 75 72 65 49 74 37 2d 73 |....PictureIt7-s| 000065a0 30 32 3a 70 9c 00 00 00 00 14 74 45 58 74 54 69 |02:p......tEXtTi| 000065b0 74 6c 65 00 50 69 63 74 75 72 65 49 74 37 2d 73 |tle.PictureIt7-s| 000065c0 30 32 f2 8f d5 89 00 00 00 00 49 45 4e 44 ae 42 |02........IEND.B| 000065d0 60 82 |`.|

What what do we have here? Near the end of the file before the IEND chunk is an OLE file with the very recognizable hex values of “D0CF11E0“. Let’s strip out the OLE file and take a look.

Path = PictureIt7-s02-ole

Type = Compound

WARNINGS:

There are data after the end of archive

Physical Size = 8704

Tail Size = 7764

Extension = compound

Cluster Size = 512

Sector Size = 64

Date Time Attr Size Compressed Name

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2023-12-26 22:01:58 D.... DataStore

2023-12-26 22:01:58 D.... Text

..... 2560 2560 Text/CONTENTS

..... 86 128 Text/[1]CompObj

..... 96 128 DataStore/3

..... 4 64 DataStore/1

..... 121 128 DataStore/0

..... 57 64 DataStore/2

..... 98 128 DataStore/5

..... 4 64 DataStore/4

..... 1254 1280 DataStore/7

..... 4 64 DataStore/6

..... 4 64 DataStore/8

------------------- ----- ------------ ------------ ------------------------

2023-12-26 22:01:58 4288 4672 11 files, 2 folders

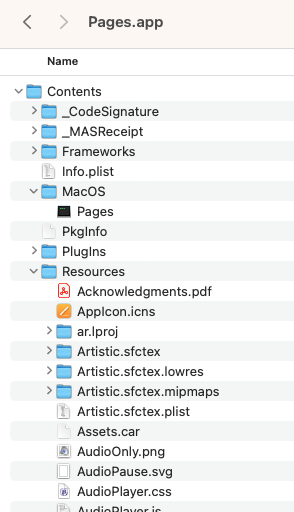

Interesting, I don’t think I have come across a standard format with a container embedded within. I have come across many OLE and ZIP containers which contain other common formats within, but this format is definitely unique. Others have added features in the IDAT chunk, such as a web shell. I am sure there are others out there. The CompObj file found within the Text directory is very similar to the Microsoft Works and Publisher format. Although trying to open the file in Publisher doesn’t work!

hexdump -C PictureIt7-s02-ole/Text/\[1\]CompObj | head 00000000 01 00 fe ff 03 0a 00 00 ff ff ff ff 00 00 00 00 |................| 00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 1a 00 00 00 |................| 00000020 51 75 69 6c 6c 39 36 20 53 74 6f 72 79 20 47 72 |Quill96 Story Gr| 00000030 6f 75 70 20 43 6c 61 73 73 00 ff ff ff ff 01 00 |oup Class.......| 00000040 00 00 00 00 00 00 f4 39 b2 71 00 00 00 00 00 00 |.......9.q......| 00000050 00 00 00 00 00 00 |......|

PRONOM uses binary and container signatures to identify file formats. Even though this file format contains a valid OLE container, because it is within a regular binary file format, I don’t believe a container signature would work. The difficulty will be to clearly identify this new format without falsely identifying a regular PNG instead. The OLE file format header is not in a consistent location to use a specific offset. Making the string a variable location can causes some undo processing, so lets look to see if there is anything else we can use to make a positive ID.

The PNG file format is based on chunks, you have to have IHDR, then an IDAT and the IEND chunk. If we take a look at a regular PNG file using a libpng tool pngcheck, we see this:

pngcheck -cvt rgb-8.png

File: rgb-8.png (759 bytes)

chunk IHDR at offset 0x0000c, length 13

256 x 256 image, 24-bit RGB, non-interlaced

chunk tEXt at offset 0x00025, length 44, keyword: Copyright

? 2013,2015 John Cunningham Bowler

chunk iTXt at offset 0x0005d, length 116, keyword: Licensing

compressed, language tag = en

no translated keyword, 101 bytes of UTF-8 text

chunk IDAT at offset 0x000dd, length 518

zlib: deflated, 32K window, maximum compression

chunk IEND at offset 0x002ef, length 0

No errors detected in rgb-8.png (5 chunks, 99.6% compression).

The required chunk are there, but a couple extra, the tEXt and iTXt, which are textual metadata you can add. Now lets look at a PNG Plus file:

pngcheck -cvt PictureIt7-s02.png

File: PictureIt7-s02.png (26066 bytes)

chunk IHDR at offset 0x0000c, length 13

500 x 333 image, 32-bit RGB+alpha, non-interlaced

chunk sRGB at offset 0x00025, length 1

rendering intent = perceptual

chunk gAMA at offset 0x00032, length 4: 0.45455

chunk cHRM at offset 0x00042, length 32

White x = 0.3127 y = 0.329, Red x = 0.64 y = 0.33

Green x = 0.3 y = 0.6, Blue x = 0.15 y = 0.06

chunk IDAT at offset 0x0006e, length 9460

zlib: deflated, 32K window, fast compression

chunk cmOD at offset 0x0256e, length 0

Microsoft Picture It private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk cpIp at offset 0x0257a, length 16384

Microsoft Picture It private, ancillary, safe-to-copy chunk

chunk iTXt at offset 0x06586, length 24, keyword: Title

uncompressed, no language tag

no translated keyword, 15 bytes of UTF-8 text

chunk tEXt at offset 0x065aa, length 20, keyword: Title

PictureIt7-s02

chunk IEND at offset 0x065ca, length 0

No errors detected in PictureIt7-s02.png (10 chunks, 96.1% compression).

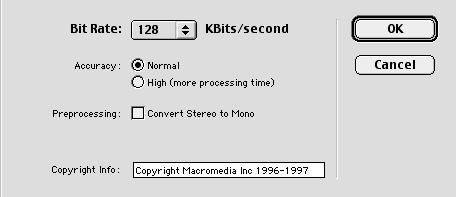

It looks like we have the required chunks and some textual chunks but also a couple chunks which pngcheck describes as private and identify’s them as Microsoft Picture It chunks. The cpIp chunk is the one which contains the OLE container. This is the chunk we need to identify in a signature. The problem is the offset for the cpIp chunk is not the same each time. Here is one from Digital Image 10 Pro.

chunk cpIp at offset 0x737a7, length 245760

Microsoft Picture It private, ancillary, safe-to-copy chunk

Significantly further in the file that the other example. These samples currently identify as PNG 1.2 files. PRONOM fmt/13 so we can use the signature and add to it, but it currently doesn’t look for IDAT only the iTXt chunk, which is probably not optimal. For PNG Plus, lets get the header which includes IHDR, IDAT, then the cpIp chunk then an end of file sequence for IEND. Take a look at my signature and samples, I am curious how many PNG Plus files are out there hidden to the world.

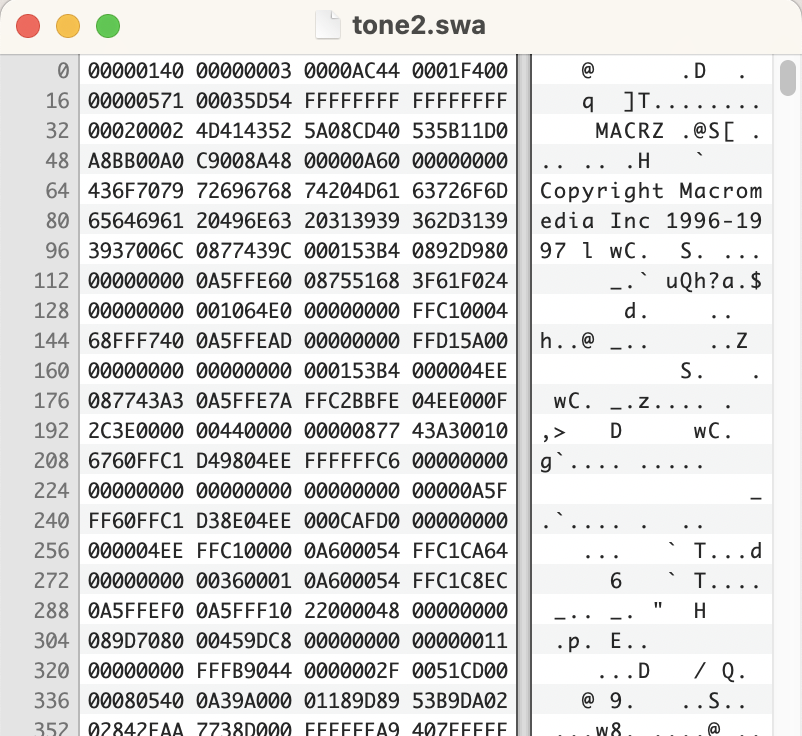

Turns out there is another PNG flavor which has been enhanced to allow for layers and pages. Adobe Fireworks uses a PNG format as their native format. They also use private chunks, but not within an OLE container. They use additional chunks, but before the IDAT chunk:

chunk prVW at offset 0x00092, length 1700

Macromedia Fireworks preview chunk (private, ancillary, unsafe to copy)

chunk mkBF at offset 0x00742, length 72

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkTS at offset 0x00796, length 36716

Macromedia Fireworks(?) private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBS at offset 0x0970e, length 190

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x097d8, length 1251

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x09cc7, length 1358

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0a221, length 1145

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0a6a6, length 339

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0a805, length 695

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0aac8, length 3799

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0b9ab, length 7733

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0d7ec, length 2741

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0e2ad, length 5153

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

chunk mkBT at offset 0x0f6da, length 10775

Macromedia Fireworks private, ancillary, unsafe-to-copy chunk

It’s hard to know which each of the chunks are for and if they are all required for the Fireworks PNG format. From the book on PNG.

In addition to supporting PNG as an output format, Fireworks actually uses PNG as its native file format for day-to-day intermediate saves. This is possible thanks to PNG’s extensible “chunk-based” design, which allows programs to incorporate application-specific data in a well-defined way. Macromedia has embraced this capability, defining at least four custom chunk types that hold various things pertinent to the editor. Unfortunately, one of them (pRVW) violates the PNG naming rules by claiming to be an officially registered, public chunk type, but this was an oversight and should be fixed in version 2.0.