I have used and have researched a lot of audio editing software. Some are very simple and straightforward, others are feature rich and take some time to learn. While looking in a format, I came across some Audio software which nothing like I have used before. At first I was confused, I figured it would be simple to open a certain file format and play the audio. Not so fast.

Max is software which proudly says it is an, “infinitely flexible space to create your own interactive software”. Created by Cycling ’74 software, Max has been around for awhile, being developed in the mid 1980’s. It allows the user to make “patches” stringing around components and effects to accomplish an infinite amount of options and outcomes.

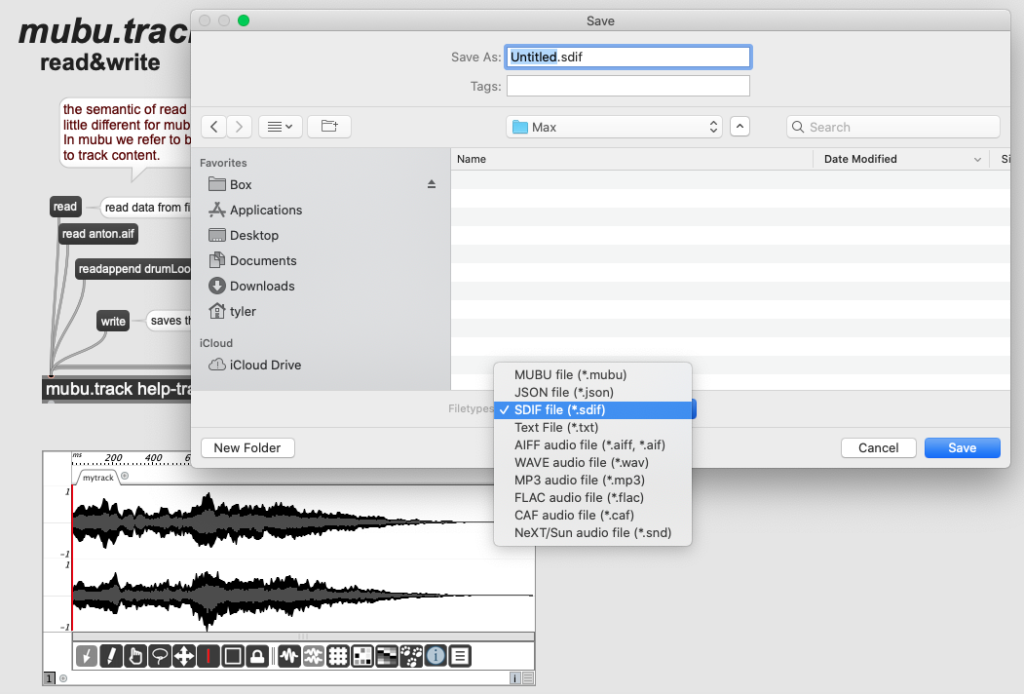

The software produces simple project files and patch files, but hey are just JSON data, at least in the latest version. But when working with audio files the software can save to a number of formats.

One of the options is a format called “SDIF”, which stands for “Sound Description Interchange Format“. SDIF was jointly developed by IRCAM and CNMAT, with proposals starting back in the mid-1990’s. Originally written as a Spectral Description, it was later changed to refer to a Sound Description.

The Specification states the general idea was to “store information related to signal processing and specifically of sound, in files, according to a common format to all data types. Thus, it is possible to store results or parameters of analyses, syntheses…” So not exactly the same as a simple WAVE file you can open and edit, this format was meant to store signal data for analysis.

Each SDIF file consists of a header and then an overall a succession of frames, not unlike chunks in the IFF/AIFF/RIFF formats, ordered in time. Each frame matrix declares a “Type” which can be a combination of many options. Lets take a look at a SDIF file:

hexdump -C test.sdif | head

00000000 53 44 49 46 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 01 |SDIF............|

00000010 31 54 52 43 00 00 00 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |1TRC... ........|

00000020 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 01 31 54 52 43 00 00 00 04 |........1TRC....|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 31 54 52 43 00 00 00 c0 |........1TRC....|

00000040 3f 74 7a e1 40 00 00 00 00 00 00 01 00 00 00 01 |?tz.@...........|

00000050 31 54 52 43 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 0a 00 00 00 04 |1TRC............|

00000060 3f 80 00 00 45 95 35 c3 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |?...E.5.........|

00000070 40 00 00 00 46 06 e2 14 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |@...F...........|

00000080 40 40 00 00 45 3b 42 3d 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |@@..E;B=........|

00000090 40 80 00 00 43 5d 94 7b 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |@...C].{........|

This test file has the opening frame “SDIF“, to identify it as an SDIF, then a reference to the type “1TRC“. I would try and explain a Matrix 1TRC Sinusoidal Track, but I have no idea what it means. Something, something sine wave, etc. Someone much smarter than me can make use of this format. Here are a couple examples of SDIF with other frame types.

hexdump -C angry_cat.part.sdif| head

00000000 53 44 49 46 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 01 |SDIF............|

00000010 31 4e 56 54 00 00 00 88 ff ef ff ff ff ff ff ff |1NVT............|

00000020 ff ff ff fd 00 00 00 01 31 4e 56 54 00 00 03 01 |........1NVT....|

00000030 00 00 00 61 00 00 00 01 53 74 72 65 61 6d 49 44 |...a....StreamID|

00000040 09 30 0a 44 61 74 65 09 54 68 75 5f 41 75 67 5f |.0.Date.Thu_Aug_|

00000050 5f 33 5f 32 31 2e 33 32 2e 34 35 5f 32 30 30 30 |_3_21.32.45_2000|

00000060 5f 0a 54 61 62 6c 65 4e 61 6d 65 09 53 69 6e 75 |_.TableName.Sinu|

00000070 73 6f 69 64 61 6c 54 72 61 63 6b 73 0a 57 72 69 |soidalTracks.Wri|

00000080 74 74 65 6e 42 79 09 50 6d 5f 56 65 72 73 69 6f |ttenBy.Pm_Versio|

00000090 6e 5f 31 2e 32 2e 32 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |n_1.2.2.........|

hexdump -C cymbalum-c4.res.sdif| head

00000000 53 44 49 46 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 01 |SDIF............|

00000010 31 52 45 53 00 00 0d 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |1RES... ........|

00000020 00 00 00 04 00 00 00 01 31 52 45 53 00 00 00 04 |........1RES....|

00000030 00 00 00 d0 00 00 00 04 42 49 27 7a 39 59 fc ab |........BI'z9Y..|

00000040 3d 35 06 c9 00 00 00 00 42 6e 68 68 39 63 99 b1 |=5......Bnhh9c..|

00000050 3e 25 f7 c0 00 00 00 00 42 c6 02 bb 39 8c 31 79 |>%......B...9.1y|

00000060 3f bb 7e 6e 00 00 00 00 43 01 82 96 3a 1d 36 44 |?.~n....C...:.6D|

00000070 3e d9 21 12 00 00 00 00 43 07 35 f0 3a 20 6f 6e |>.!.....C.5.: on|

00000080 3f 02 32 7f 00 00 00 00 43 30 84 0b 39 97 f9 1b |?.2.....C0..9...|

00000090 3e c6 43 c7 00 00 00 00 43 4d e4 e4 39 88 14 90 |>.C.....CM..9...|

Unfortunately, the common tools I use to explore AV formats don’t seem to work on this format. MediaInfo, FFProbe, Exiftool, all give me unknown file warnings. So I had to compile the SDIF software in order to get some details.

querysdif angry_cat.part.sdif

Header info of file angry_cat.part.sdif:

Format version: 3

Types version: 1

Ascii chunks of file angry_cat.part.sdif:

1NVT

{

StreamID 0;

Date Thu_Aug__3_21.32.45_2000_;

TableName SinusoidalTracks;

WrittenBy Pm_Version_1.2.2;

}

Data in file angry_cat.part.sdif (9504872 bytes):

1933 1TRC frames in stream 0 between time 0.000000 and 5.794875 containing

1933 1TRC matrices with 45 --400 rows, 4 -- 4 columns

An interesting thing is that a SDIF file can be in text form as well.

sdiftotext test.sdif

SDIF

SDFC

1TRC 1 1 0

1TRC 0x0004 0 4

1TRC 1 1 0.005

1TRC 0x0004 10 4

1 4774.72 0 0

2 8632.52 0 0

3 2996.14 0 0

4 221.58 0 0

5 1943.02 0 0

6 123.951 0 0

7 6705.04 0 0

8 4304.97 0 0

9 3554.29 0 0

10 23.7822 0 0

1TRC 1 1 0.01

1TRC 0x0004 10 4

1 4774.72 0.0353114 2.06098

2 8632.52 0.00442518 0.68795

3 2996.14 0.0238517 -1.42295

4 221.58 0.0089712 -2.44141

5 1943.02 0.00768914 2.64629

6 123.951 0.0397061 -0.17527

7 6705.04 0.0245643 -0.168753

8 4304.97 0.00894803 1.45553

9 3554.29 0.0265175 2.57231

10 23.7822 0.0419019 -2.17731

1TRC 1 1 0.2

1TRC 0x0004 10 4

1 2284.56 0.02781 2.47054

2 4222.62 0.0151738 1.55309

3 31.1554 0.00421461 -0.657285

4 310.99 0.0122306 1.25794

5 215.192 0.0174093 1.25468

6 6253.69 0.000894192 2.21334

7 8533.32 0.0296167 2.07209

8 8044.77 0.0423002 2.54088

9 6087.45 0.0264733 -2.05523

10 7052.7 0.0287347 0.426339

1TRC 1 1 0.205

1TRC 0x0004 10 4

1 2284.56 0 0

2 4222.62 0 0

3 31.1554 0 0

4 310.99 0 0

5 215.192 0 0

6 6253.69 0 0

7 8533.32 0 0

8 8044.77 0 0

9 6087.45 0 0

10 7052.7 0 0

1TRC 1 1 0.21

1TRC 0x0004 0 4

ENDC

ENDF

An interesting format for sure. But wait, there is more!

My initial interest in this format was when I was given access to a set of MUBU files. I was unclear on how there were created at first and it took me down a long path of learning about SDIF and the Max software from Cycling ’74 and IRCAM. MUBU turns out to be a toolbox for Max which adds more analysis features.

MUBU stands for MUlti-BUffer, which helps overcome some limitations. It is actually a container using the SDIF standard. Lets take a look.

hexdump -C test.mubu | head

00000000 53 44 49 46 00 00 00 08 00 00 00 03 00 00 00 01 |SDIF............|

00000010 31 4e 56 54 00 00 00 78 ff ef ff ff ff ff ff ff |1NVT...x........|

00000020 ff ff ff fd 00 00 00 01 31 4e 56 54 00 00 03 01 |........1NVT....|

00000030 00 00 00 53 00 00 00 01 4d 75 42 75 2e 43 6f 6e |...S....MuBu.Con|

00000040 74 61 69 6e 65 72 2e 4e 75 6d 54 72 61 63 6b 73 |tainer.NumTracks|

00000050 09 31 0a 4d 75 42 75 2e 43 6f 6e 74 61 69 6e 65 |.1.MuBu.Containe|

00000060 72 2e 56 65 72 73 69 6f 6e 09 31 2e 35 0a 4d 75 |r.Version.1.5.Mu|

00000070 42 75 2e 43 6f 6e 74 61 69 6e 65 72 2e 4e 75 6d |Bu.Container.Num|

00000080 42 75 66 66 65 72 73 09 31 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 |Buffers.1.......|

00000090 31 4e 56 54 00 00 00 38 ff ef ff ff ff ff ff ff |1NVT...8........|

A MUBU file has the same SDIF frame header, but also include a “1NVT” frame, which is a Name Value Table. This is where the MUBU container is referenced. The MuBu file has its own structure:

If I query the MuBu file like I did the SDIF, I get the following:

querysdif test.mubu

Header info of file test.mubu:

Format version: 3

Types version: 1

Ascii chunks of file test.mubu:

1NVT

{

MuBu.Container.NumTracks 1;

MuBu.Container.Version 1.5;

MuBu.Container.NumBuffers 1;

}

1NVT

{

MuBu.Buffer.Index 0;

}

1NVT

{

MuBu.Track.MxRows 2;

AudioFile 1;

MuBu.Track.NonNumType 0;

MuBu.Track.MaxSize 93515;

meta_ISFT Lavf60.16.100;

MuBu.Track.Name mytrack;

MuBu.Track.BufferIndex 0;

MuBu.Track.SampleRate 48000;

FileName Wilhelm_Scream.wav;

MuBu.Track.MxVarRows 0;

MuBu.Track.MxCols 1;

meta_MetaDataSource WAV;

MuBu.Track.EndTime 1623.5;

FilePath /;

MuBu.Track.SampleOffset 0;

MuBu.Track.TimeTags 0;

MuBu.Track.Size 77929;

MuBu.Track.Index 0;

}

1TYP

{

1MTD M000 {unnamed}

1FTD M000

{

M000 Track-0-MatrixData;

}

}

Data in file test.mubu (3741392 bytes):

77929 M000 frames in stream 0 between time 0.000000 and 1.623500 containing

77929 M000 matrices with 2 -- 2 rows, 1 -- 1 columns

The MuBu file contains one audio track and one buffer. This is a simple test file, but MuBu files can be quite large with multiple tracks.

Working with the Max software or OpenMusic is not something I found to be easy to understand. I am sure if I was more musically inclined and with a little practice I could make some of this work. For the time being, a signature to identify a SDIF and MUBU will have to do. Check out the GitHub for my proposed signature and a couple examples.