PagePerfect: the Promise of Desktop Publishing Realized

Now, PagePerfect has arrived. And suddenly PC desktop publishing is a lot

simpler and less expensive, because PagePerfect integrates desktop

publishing, word processing, and graphics editing all in one package.

The 1980’s was a time of growth in personal computing and one industry was progressing rapidly. Previously in order to get printed more than just words, you had to use a complex arrangement of type, masking, screening; all done by hand. Now with a personal computer you could design and print well designed layouts. There were many software applications who came on the scene in these early days. My personal favorite was QuarkXPress, I used the software in the early 1990’s and spent the next few years working in a commercial printshop using the software. What once took a team of skilled workers to set copy, mask, blueline, etc took only one person with the right software.

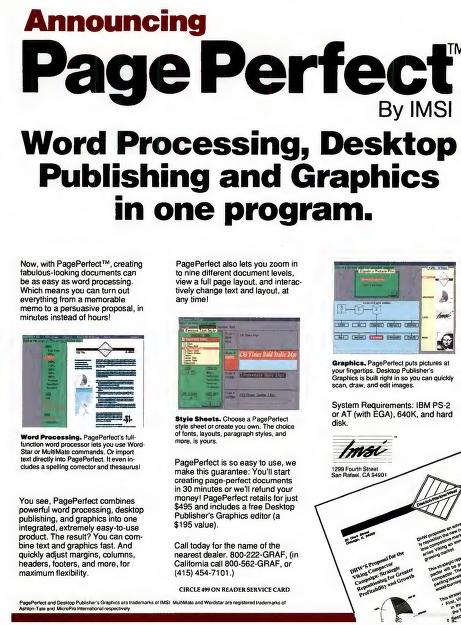

I recently came across a set of floppy disks for some software called PagePerfect, by a well known software company IMSI.

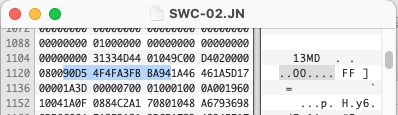

This article in a 1988 PC Magazine announces this new revolutionary software. This was early on in the days of computer desktop publishing and even on a DOS system the software was powerful. It didn’t always get the best reviews in terms of ease of use, but it was well built. The company behind this powerful software wasn’t IMSI as you might expect, it was programed by a different company, Beyond Words, started by three former MicroPro employees, the makers of WordStar. Beyond Words liked to “leave sales to others” which included IMSI and a big contract with Canon called their Desktop Publishing System.

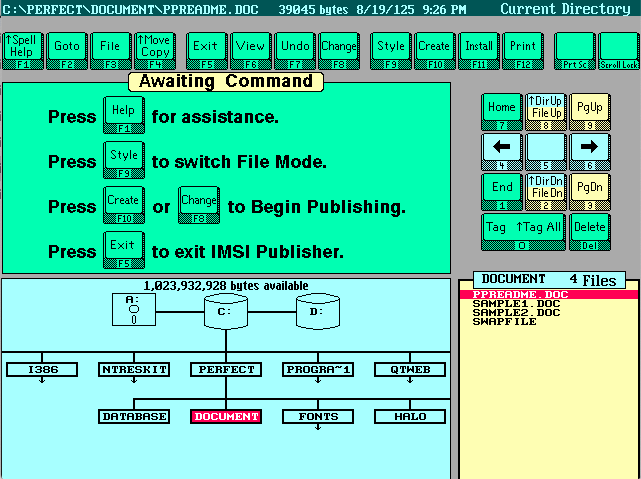

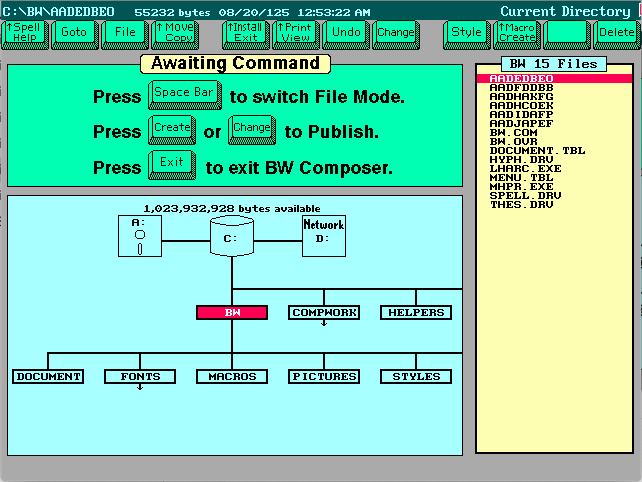

IMSI was able to market the software well and was well priced. The name PagePerfect didn’t last long and soon after they renamed the software IMSI Publisher in 1989. I’m not 100% sure, but it might have to do with WordPerfect asserting some copyright to the name around that same time. By 1990, the software was not seen much anymore, but another name pops up, Beyond Words Composer 2.0.

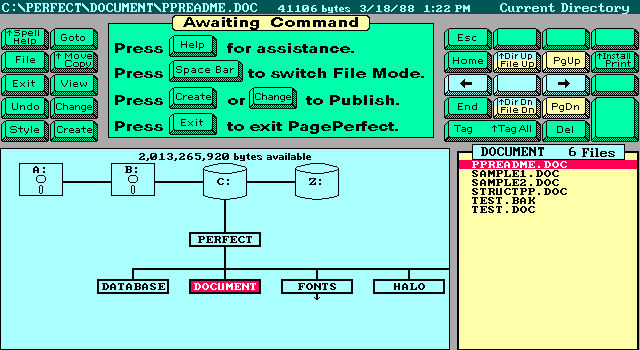

All three versions of the software have a very similar interface.

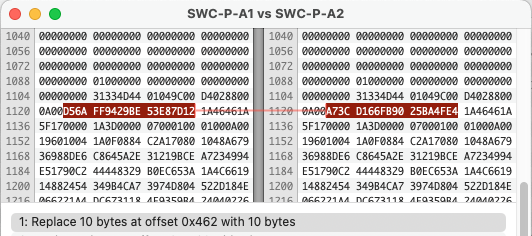

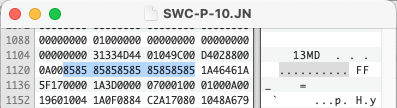

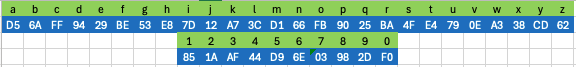

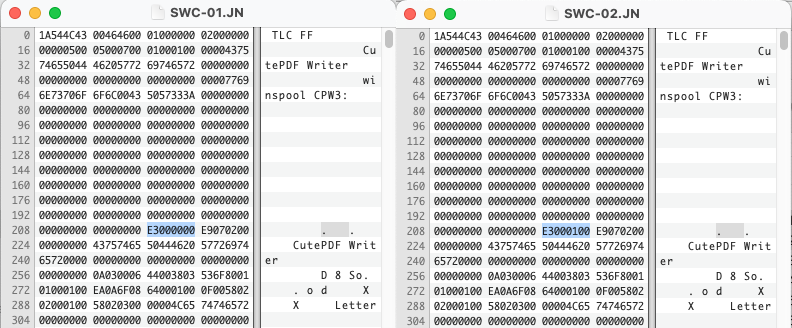

But the one thing they all have in common is their file formats. Unfortunately they used the same extensions many word processing software used during this time and after. .DOC and also .STY which was used frequently by Microsoft Word as well. It makes sense, a Document is shortened to DOC and a Stylesheet is shortened to STY. So if you have any DOC files which don’t open in Word, you might look here. The other problem is the file format used is not plain text and is in a binary proprietary format.

hexdump -C TEST.DOC | head

00000000 5b 42 57 44 42 5d 00 00 00 00 00 31 2e 30 30 00 |[BWDB].....1.00.|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 3c af 13 5b 1e 00 00 00 95 63 |......<..[.....c|

00000020 00 00 5e 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 01 00 76 00 00 00 |..^.........v...|

00000030 68 01 00 00 0a 00 de 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |h...............|

00000040 de 01 00 00 8b 60 00 00 1e 00 69 62 00 00 2c 01 |.....`....ib..,.|

00000050 00 00 1e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 5b 42 |..............[B|

00000060 57 44 4f 43 5d 00 00 00 00 32 2e 30 39 00 00 00 |WDOC]....2.09...|

00000070 00 00 00 00 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000080 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000090 00 00 00 00 6c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |....l...........|

The one positive is the very obvious strings of text in the header. [BWDB] and [BWDOC], which one could infer as Beyond Words DB and Beyond Words Document. A later Beyond Words Composer document has the same header but a higher version number.

hexdump -C WELCOME.DOC | head

00000000 5b 42 57 44 42 5d 00 00 00 00 00 31 2e 30 30 00 |[BWDB].....1.00.|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 aa 14 56 16 29 00 00 00 30 84 |........V.)...0.|

00000020 00 00 5e 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 01 00 76 00 00 00 |..^.........v...|

00000030 b0 01 00 00 0c 00 26 02 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |......&.........|

00000040 26 02 00 00 70 80 00 00 29 00 96 82 00 00 9a 01 |&...p...).......|

00000050 00 00 29 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 5b 42 |..)...........[B|

00000060 57 44 4f 43 5d 00 00 00 00 33 2e 30 31 00 00 00 |WDOC]....3.01...|

00000070 00 00 00 00 0c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000080 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000090 00 00 00 00 6e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |....n...........|

If we look at the Stylesheets we see the same patterns.

hexdump -C SAMPLE.STY | head

00000000 5b 42 57 44 42 5d 00 00 00 00 00 31 2e 30 30 00 |[BWDB].....1.00.|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 51 10 76 10 09 00 00 00 da 2c |......Q.v......,|

00000020 00 00 5e 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 01 00 76 00 00 00 |..^.........v...|

00000030 68 01 00 00 0a 00 de 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |h...............|

00000040 de 01 00 00 a2 2a 00 00 09 00 80 2c 00 00 5a 00 |.....*.....,..Z.|

00000050 00 00 09 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 5b 42 |..............[B|

00000060 57 44 4f 43 5d 00 00 00 00 32 2e 30 39 00 00 00 |WDOC]....2.09...|

00000070 00 00 00 00 0a 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000080 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000090 00 00 00 00 6c 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |....l...........|

I haven’t been able to find any specific bytes which differentiate the Stylesheets from the Documents. They may be the same format, but for now we will consider them the same. These stylesheets seem to function as a template which are often the same format.

Apart from the document layout, the software can also create and use databases. Which appear to be a similar format but with different offsets.

hexdump -C DOCUMENT.TBL | head

00000000 5b 42 57 44 42 5d 00 00 00 00 00 31 2e 30 30 00 |[BWDB].....1.00.|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 6b 10 36 00 00 00 18 00 00 00 |......k.6.......|

00000020 01 00 4e 00 00 00 68 01 00 00 0a 00 b6 01 00 00 |..N...h.........|

00000030 00 00 00 00 00 00 5b 42 57 44 4f 43 5d 00 00 00 |......[BWDOC]...|

00000040 00 32 2e 30 39 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 0a 00 00 00 |.2.09...........|

00000050 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

00000060 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 6c 00 00 00 |............l...|

00000070 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

Prior to me diving into this format, the only tool which had some information on this format was TrID, which identified all the DOC and STY files as Beyond Words Composer style. Which is mostly true. Hopefully with this background you can be aware of the different software names this format was used with and with some luck convert the files to something less proprietary.

Some disks that came with my PagePerfect install disks do have some personal documents created with the software, but I wonder how much this software really was used in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, because after that point, you don’t hear about the software anymore. There is some references to the software getting absorbed into another software, IBM DisplayWrite 5/2. I would be curious if others have come across this file format.