Working with files in todays world is much different than before. Today getting files back and forth from the cloud or through email is relatively easy, unlike the early days when we used FTP sites and needed to encode our data to properly transfer. I remember using an FTP program on my old Mac called Fetch. We had to determine if the content was to be transferred as text or binary.

Picking the right encoding was critical to getting the content transferred correctly, this was even more critical when working with Macintosh files which needed a resource fork and/or finder attributes to work properly. In those cases a MacBinary or BinHex file was required! Fetch would automatically identify those formats and decode them for you.

If you need a refresher on MacBinary and AppleSingle, you can view my iPres 2022 presentation.

One format I didn’t spend much if any time on is the BinHex format. BinHex was a format born out of necessity to move files back and forth across the World Web Web, bulletin boards, AOL, Compuserve, and the like. The FTP program Fetch glossary describes BinHex as:

BinHex (sometimes called BinHex4) is a format for representing a Macintosh file in text form.

The Macintosh file is converted to a series of lines, each made up of letters, numbers, and

punctuation. Because BinHex files are simply text, they can be sent through most electronic mail

systems and stored on most computers. However the conversion to text makes the file larger, so it

takes longer to transmit a file in BinHex format than if the file was represented some other way.

The suffix “.hqx” usually indicates a BinHex format file.

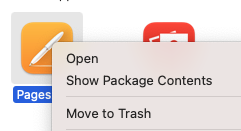

You can still find many of these HQX files floating around the interwebs and on older CDs from the 1990’s. One such CD recently came into my possession. I managed to get a copy of the book “Internet File Formats“, by Tim Kientzie. It came with a CD-ROM with lots of goodies included. Some sample files, specifications, and software. The disc itself is an ISO 9660 partitioned disc, but includes a few Macintosh formats, so the author put many of the software files in the HQX format to maintain the much needed resource fork Macintosh applications need in order to run.

I initially ran the whole disc through DROID to get an idea what was on the disc and if any sample formats were unidentified (something I do regularly), and found majority of the HQX files didn’t identify as they should have to PRONOM PUID x-fmt/416. The signature is an older one, from 2010, but since the format isn’t updated anymore it should be solid. Or so I thought.

Since BINHEX files are encoded as text, lets take a look at a couple of these from the disc which didn’t identify.

The PRONOM signature currently is:

File extension: hqx Name BinHex Binary Text Description Header: (This file must be converted with BinHex Byte sequences Position type Absolute from BOF Offset 0 Value 28546869732066696C65206D75737420626520636F6E76657274656420776974682042696E486578

That “Value” listed in hexadecimal decodes to: “(This file must be converted with BinHex” as listed in the description. We can see this line in the file above, but the signature assumes the value begins at offset 0 from the beginning of the file. So its looking for that value at the start of the file, but this file seems to have some additional text before the value. What does the specs say?

The BinHex 4.0 format was created in 1985 and defined in RFC 1741.

The whole file is considered as a stream of bits. This stream will

be divided in blocks of 6 bits and then converted to one of 64

characters contained in a table. The characters in this table have

been chosen for maximum noise protection. The format will start

with a ":" (first character on a line) and end with a ":".

There will be a maximum of 64 characters on a line. It must be

preceded, by this comment, starting in column 1 (it does not start

in column 1 in this document):

(This file must be converted with BinHex 4.0)

Any text before this comment is to be ignored.

The characters used is:

!"#$%&'()*+,- 012345689@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNPQRSTUVXYZ[`abcdefhijklmpqr

Ok, so in the specs we can see the “Value” string must be there, but according to the specification, any text before this comment is to be ignored. So adding some instructions and even an email header at the beginning is ok, as long as the value string is there right before the encoded data.

We also learn a couple interesting things. The first character of the first line after the string should be a “:” and the last line should end with a “:” as well. That could help make the signature more solid. We also learn there are a maximum of 64 characters per line. The last line will probably not have full maximum, but the previous lines should…. I wonder if we could use this fixed position from the initial “:” to add even more strength to the signature.

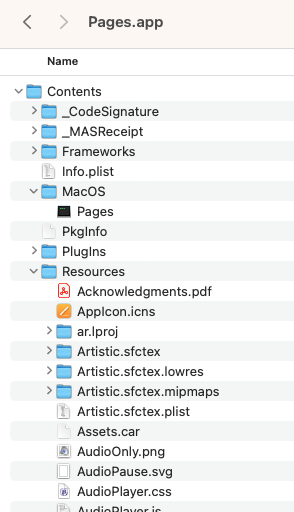

So an updated PRONOM signature might look like:

BOF: {0-4084}28546869732066696C65206D75737420626520636F6E76657274656420776974682042696E486578{6-9}3A

EOF: 3A (Max Offset 64)

Adding the 4,084 bytes at the beginning allow for additional text. This value worked for my samples but there could be others out there with more. The {6-9} bytes in between the string and the colon account for the various way newlines are encoded. Sometimes is one “0A” byte, other times it is “OD”, and others its both. After testing, adding values in the signature to account for the 64 byte line can fail if the file has only one line, so I left it out.

The EOF should just be the colon (3A), but I found many of my samples had various line endings and other random characters. Hence the 64 bytes for max offset.

Also, the current PRONOM entry doesn’t include the Mime-Type, which is: “application/mac-binhex40”

Hopefully this update will add some strength to the signature and follow the specification closer. The new signature even works on files with extra content at the beginning!

There are a number of software titles you can use to encode and decode a BinHex file. On a modern Mac, try using The Unarchiver, or Stuffit Expander. From the commandline, you can use the macutil library or the CLI version of Unarchiver. Although the MacOS has a built in utility to decode BinHex files. If you are using a classic version of Macintosh OS, you can find a number of utilities on Macintosh Garden.

Oh, and also, the CD-ROM I mentioned earlier has a few “fun” features. Not sure if they are on purpose or if errors were made during mastering, but a few filenames have some hidden extra characters and one folder puts any tool traversing the directory into a loop, even droid. Have fun!